Sometimes sequestered, sometimes packed together, prisoners sentenced to death generally endure harsher conditions than the rest of the prison population. For prison administrations, the terms of reference are clear: keep them alive until their execution. Budgets are tight and prisoners under death sentence are only in prison temporarily, at least on paper. In reality, they sometimes spend decades incarcerated, poorly housed and fed, barely cared for, and often secluded and marginalised.

A thousand and one deprivations¶

In Mauritania, Cameroon, India and the DRC, condemned prisoners are detained in the remotest facilities. This isolation has serious repercussions for their meagre contact with the outside world. Families, lawyers, interpreters, consular representatives, and external advocates reduce their visits or, due to limited means, discontinue their visits altogether.

Isolated from the outside, isolated inside. In Belarus, Japan, Malaysia and Pakistan, prisoners sentenced to death are placed in solitary confinement, cut off from all communication with the rest of the prison population.

”The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is there to help us. Three people sentenced to death have already died since I arrived here. We are kept apart because we are considered enemies of the nation.“

— Anna, a prisoner sentenced to death in Maroua, Cameroon.¶

The cells in which prisoners sentenced to death live are generally cramped. They may be individual, as in Japan, or shared by two condemned prisoners, as in Belarus. In the most overpopulated prisons of Pakistan and Cameroon, the size of the cell does not influence how many prisoners it holds.

The environment is harsh. In one place, the light is always on. In another, there are no light bulbs, only darkness. Small windows may let a few rays of natural light in, but rarely enough. The small cells and lack of ventilation make the heat intolerable. The amenities vary from country to country. In Belarus, the cells are furnished with a bunk, a table, chairs, and sanitary facilities, all bolted to the floor. In certain DRC facilities, prisoners must pay for their mattress or purchase one from the outside. Most prisoners sleep on mats, cardboard, bags filled with leaves, or the floor.

In Cameroon, India, Indonesia and Malaysia, soap is a rare commodity. Only prisoners who work can afford it, unless they are lucky enough to have visitors that bring it to them. In places where access to sanitary facilities is more routine, other obstacles surface. Simply taking a condemned prisoner to the shower becomes a painstaking ordeal and implies significant security measures.

Prisoners sentenced to death may spend several years surviving on food low in nutrition and variety: rice, corn, peanuts, and barley, sometimes mashed and often without anything to accompany it. Some prisoners have limited access to meat and some fruits or vegetables, obtaining them only on holidays or when relatives have permission to bring them. Though these visits are rare, they are sometimes the only defence against malnutrition. When they are forbidden or not an option, as the period of incarceration continues to drag on, health problems worsen and accumulate.

A morbid void¶

Prisoners sentenced to death wait permanently, their lives suspended between four walls. Often devoid of activity and far from loved ones, the days drag on, and the nothingness of daily life takes hold. Enough to drive anyone crazy.

Prisoners’ days all follow one after the other, but they differ from country to country. Belarus and Japan punish regular prisoners who refuse to work, but prisoners sentenced to death are forbidden from exercising any type of activity. Deprived of freedom, deprived of activity, deprived of everything, prisoners under death sentence are forced to endlessly twiddle their thumbs, forbidden from making the slightest movement, or producing the slightest sound. Elsewhere, as in India or Pakistan, training is possible, and many people take advantage of it as a means to battle boredom, use their knowledge in prison, or obtain a pardon.

“I knew that this would be a waste of my time, so I thought I might as well do something. During this time, I decided I should better myself and complete my education. I started by learning the Quran, then I finished my schooling. I completed my matriculation and intermediate (equivalent to high school) (…). These hobbies provided some solace and hope.”

— Safeer, sentenced to death, spent 18 years in prison before being released on bail while waiting to appear before the Pakistan Supreme Court.¶

Contact with the outside world is rare. Belarus and Japan prohibit phone calls, and letters are subject to censorship. In Malaysia, receipt of a letter replaces a visit.

When families manage, despite everything, to visit their relative sentenced to death, they also pay a steep price. Visits of varying length, and sometimes for a fee, may be granted one to three times per week on average. Condemned prisoners who have a child on the outside do not receive special visits. Yet, their children are the first to suffer from a severed relationship.

Visits often take place under conditions incompatible with privacy and human dignity. In India, the visits last between 20 and 30 minutes in a common room where everyone attempts to speak the loudest in order to be heard. Humiliation is par for the course during admission to the visiting rooms. In Indonesia, women have reported being forced to remove their sanitary protection before visits.

A vow of silence weighs heavily on the families. They endure considerable financial and social hardship without being able to acknowledge it publicly. When a relative is sentenced to death, the families bear the brunt. Some are forced into exile to avoid external retaliation. Others stop visiting for fear of being arrested.

The suffering body and soul¶

Prisoners sentenced to death experience deteriorating health as the months and years go by. The prison regime produces considerable physical and mental anguish. Besides, maintaining good health is far from a priority. Their fate, theoretically sealed, does not warrant the attention of the authorities.

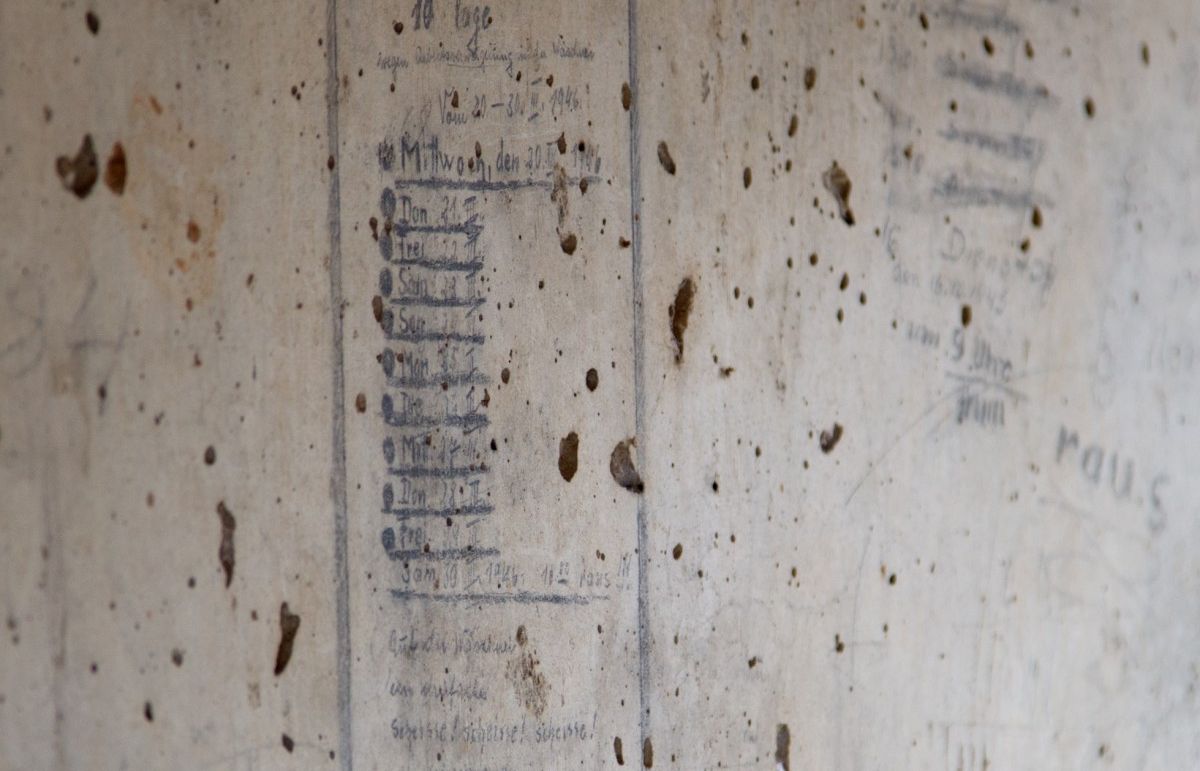

Days devoid of meaning follow one another. Condemned prisoners are permanently subject to security measures. They fall into a state of constant nervous tension. In Malaysia, prisoners under death sentence are continuously monitored. Sanitary facilities are visible from outside the cell. In Japan, these prisoners may be subjected to ’chobatsu’, a punishment that entails confining an individual for two months in handcuffs and making them eat like an animal. In Cameroon, prisoners sentenced to death may be placed in solitary confinement for a period of 10 to 15 days and are sometimes put in chains or deprived of food. Often, a payment must be made to put an end to the disciplinary measures. Overpopulation leads to the rapid spread of infection, and the resulting illnesses rarely receive treatment. If an infirmary does exist, it remains largely inaccessible to prisoners sentenced to death. Diagnoses are delayed, and the wait for transfers is endless and sometimes impossible. In Malaysia and the DRC, treatment is the same for everyone and for all ailments: acetaminophen.

The body, run down from imprisonment, must additionally endure mental illness.

Mental illness does not spare prisoners from being imposed a death sentence. Psychiatric evaluations are not automatic, and numerous failures regularly lead to the sentencing and execution of mentally ill prisoners, despite legal provisions in Belarus and Pakistan, for example.

Many prisoners sentenced to death slowly descend into madness. Others develop anxiety disorders, and some contemplate suicide. Dying before their time? Out of the question. Measures are often put in place to prevent it. Given the lack of medical staff, it would be disingenuous to speak of preventive measures. Suicide prevention falls under discipline, even more so once the execution date has been announced, representing a turning point. In Pakistan and India, prisoners are then placed in solitary confinement, and their meals are served under tighter controls. Malaysia serves meals without bones.