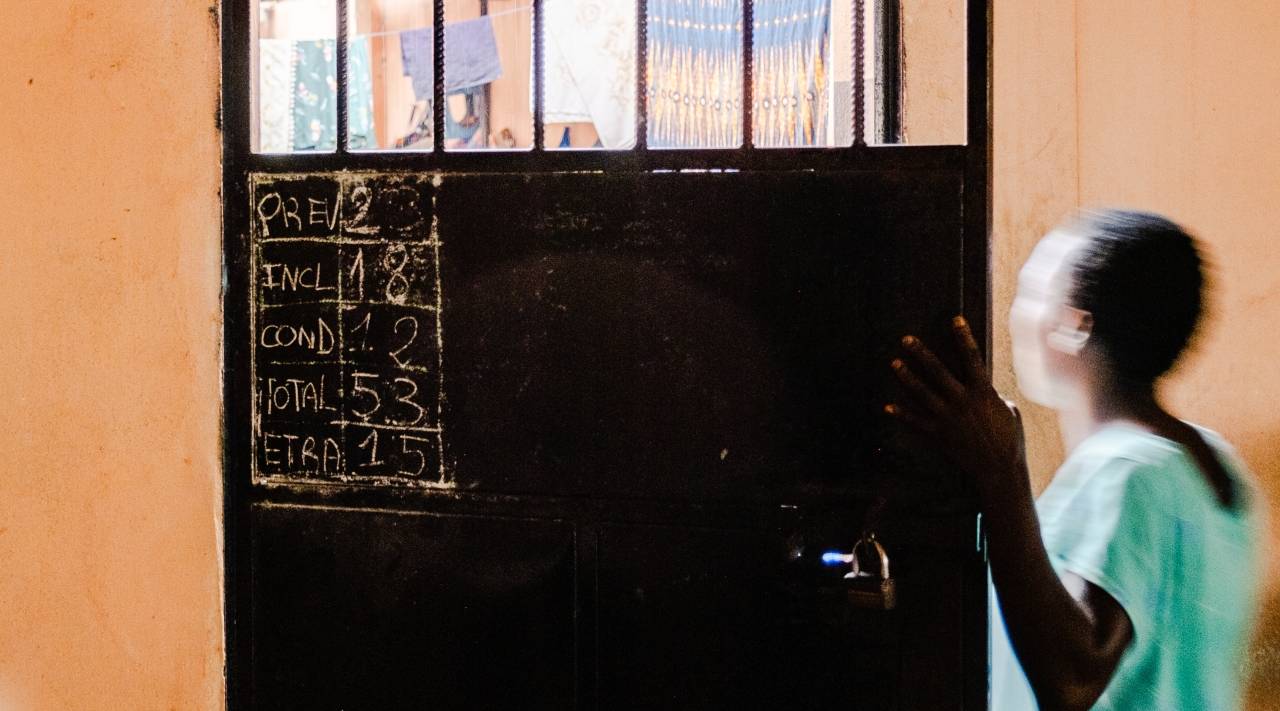

I took this image in the women’s section of a prison in West Africa. I chose it because it illustrates a number of things about both photography and human rights, and also the use of cameras in detention monitoring that I think are worth discussing.

First, in relation to photography: when I took this image I was crouching down. I did this on purpose. By starting low and shooting upwards we can give power and agency, even to people in situations of extreme vulnerability. Often we shoot down at people, which makes them look small and emphasises their status as victims. So the angle we choose as photographers is important. The second thing was the door and the light outside of it. By choosing the moment when this woman opened the door, I was able to suggest a story of hope. As a viewer we project people in images forward in space and time. But for that to happen there has to be space in the image for them to move into. How we choose the space we leave to people in our images, where the light is, and their direction of travel makes a big difference. All these things can help us tell hopeful (or not hopeful) human rights stories, even in difficult circumstances. The important thing, I think, is to be explicit in our acts and intentions.

A number of considerations from human rights work and trauma informed interviewing inform my photographic work, and this image in particular. Taking a photo is not just a moment but a process that requires preparation, to understand the context and the people you want to photograph, and follow-up. In the moment you actually decide to take a photo, you then need to take into account specific elements to frame the situation:

-

Safety. Yours, that of the person you’re photographing, both physical and psychological. Do you feel comfortable? Is this a good time? Is this a good place? You need to pay attention to verbal and non-verbal signs.

-

Control. The person you’re photographing needs to be given control of the situation. They must know they have the option to be there or to leave, to give or to withdraw their consent at any time.

-

Reflecting. You must repeat back what the person you are photographing has told you about their story, so that they know you have heard them. It must be actively said, using their own words: “I want to make sure I heard you. You said …”.

-

Closure. You must finish the process with clarity and care, you must be clear about what is happening next.

This brings me back to the question of monitoring. Many detention monitoring bodies struggle with the issue of whether they can or should bring cameras with them on their visits. Often the answer defaults to photographing only material conditions and not people. Because this is easy. There are no issues around ethics and consent, for one. But material conditions are just a limited slice of what is important in detention. By engaging with questions about what we want to achieve with photography in detention and how we can tell these stories safely and ethically, we can all contribute to telling richer and more powerful stories.