“I don’t feel safe in prison, since I am in a closed room. I also worry about my loved ones, since I am not close to them and I cannot help them in any way.”

These are the words of an incarcerated man being held near Mykolaiv as he explains the anxieties the war has brought. He is one of thousands across Ukraine, some in close proximity to the front lines, who are serving their prison sentences amongst the backdrop of the conflict.

My desire to visit and photograph prisons in Ukraine began as a question upon seeing countless images of people fleeing the country in the first weeks and months of the invasion in 2022. What happens to people in prison when a country goes to war? This then led to follow-up questions about how the war affected those inside: did they feel safe in prison? Were they able to maintain contact with family members on the outside? And more broadly, what were their thoughts on the war being fought around them?

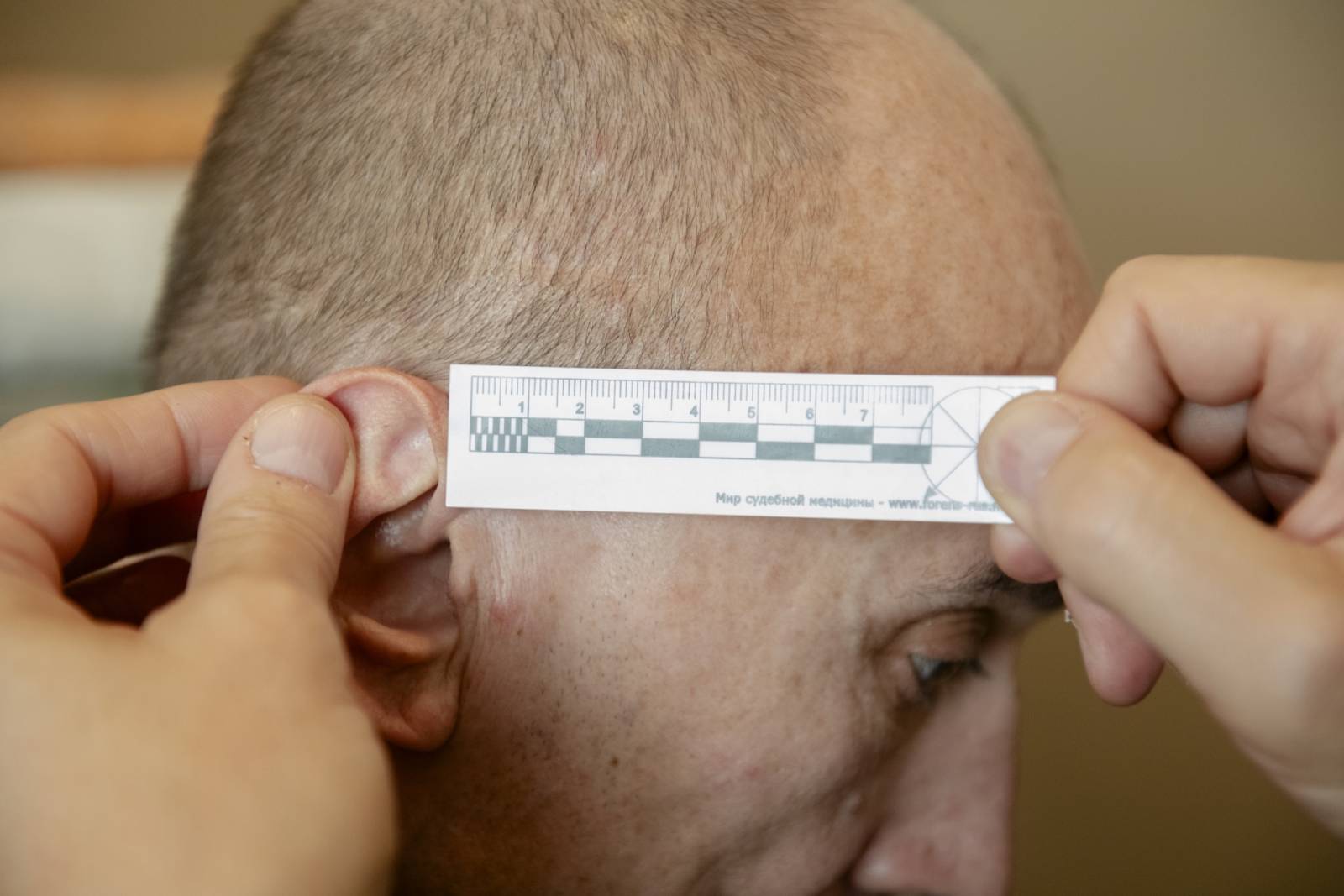

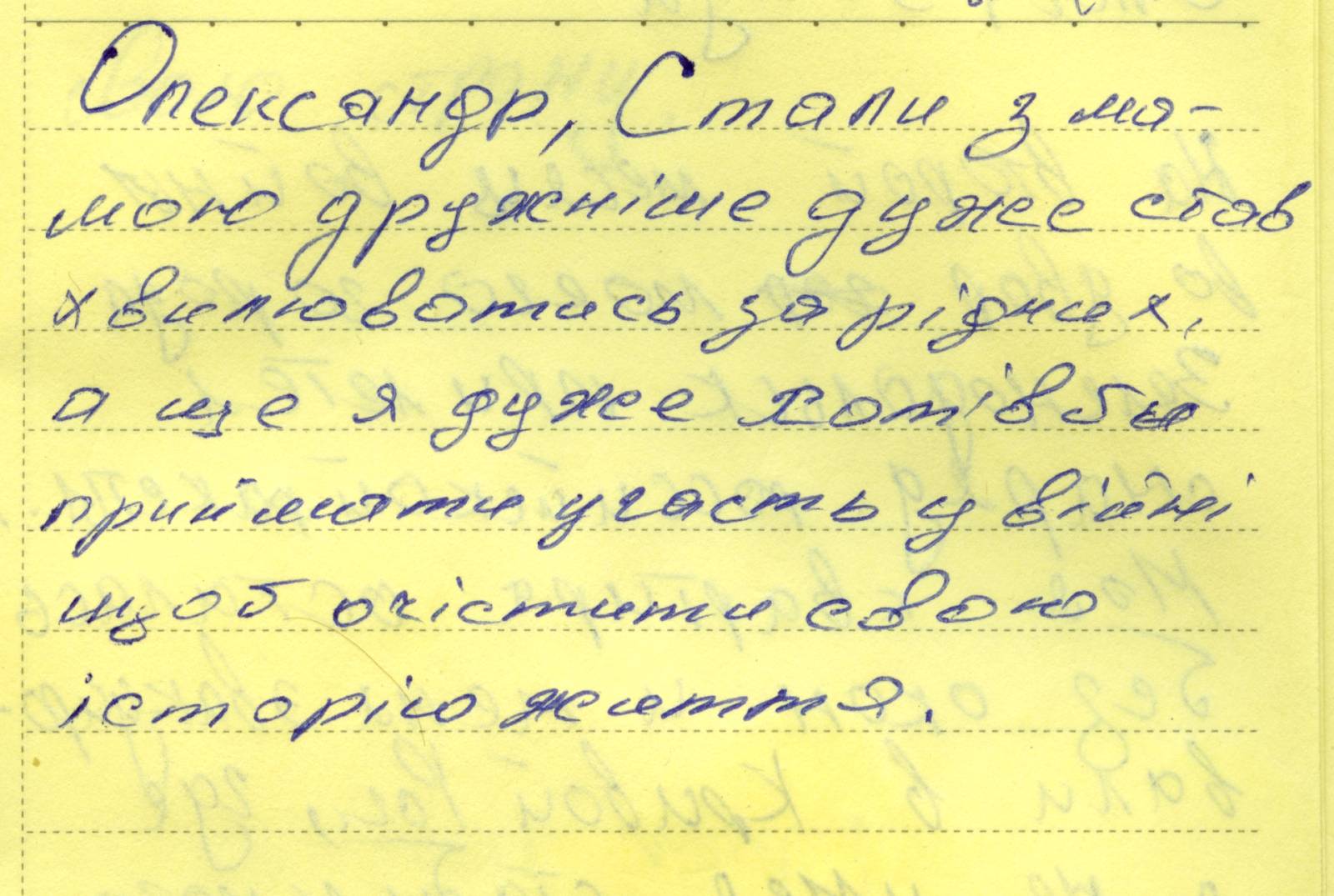

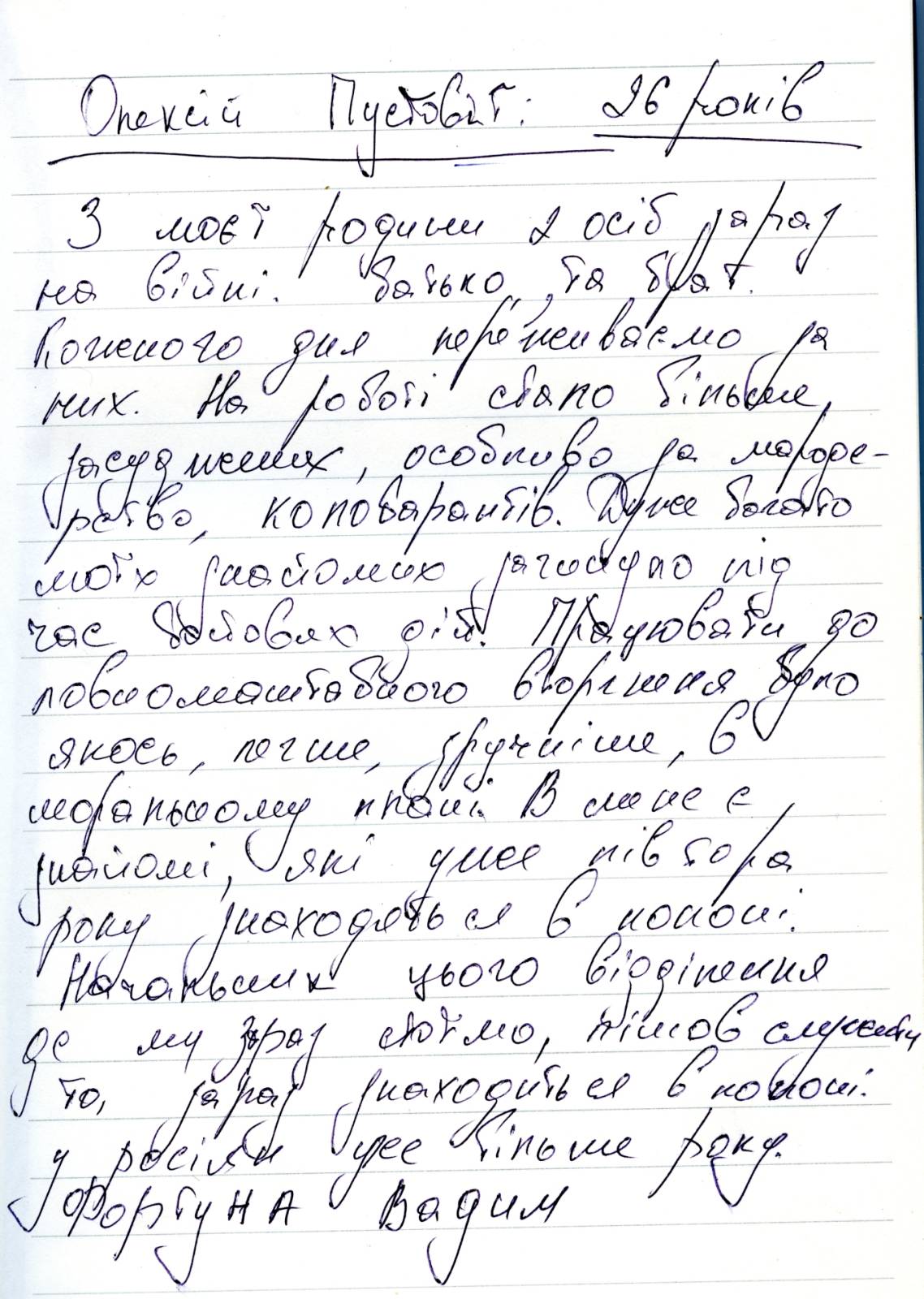

I made visits to four prisons across the country, in Mykolaiv, Kryvyi Rih, Kharkiv and Izyaslav. I was unsure of what restrictions would be imposed when entering each institution, but was certain that mobile phones (and therefore the ability to translate in real time) would not be permitted. Anticipating this, I used travel time to translate questions from English to Ukrainian and write them in a notebook which I could then show both prisoners and guards at each institution and ask for their responses. It was not ideal, but given the time and budget constraints (this being a self-funded project) it was the best I could do.

Unsurprisingly, I found that regardless of location and proximity to the front lines, all of the prisons and prisoners had somehow been affected by the conflict. Some of the prisoners I met recounted their experiences at the hands of Russian forces when their prison was overtaken in the early weeks of the conflict while others — who had not been caught in the conflict — shared worries about their family members and their well-being throughout the course of the war. In the prisons near Kharkiv, Mykoliav and Kryvyi Rih — where air raid sirens reminded prisoners and guards of the constant threat — the anxiety and uncertainty were much more palpable than in Izyaslav in the west of Ukraine. However, regardless of location there was a common sentiment echoed in all of the prisons I was able to visit: frustration at their inability to join the war and fight.

What was surprising were the responses from officers. Prison officers, guards and prison staff are amongst the lowest-paying civic duty positions (compared to police, military and firefighting for example) in Ukraine. And yet those at institutions in Mykolaiv, Kryvyi Rih, Kharkiv and Izyaslav all expressed the need to fulfil their duty despite the constant threat of airstrikes and possibility of an advancing front-line. While some officials had left to fight in the early stages of the war, the vast majority chose to stay.