Notes on confinement

Three years to go: 156 weeks; 1,092 days; 26,208 hours; 1,572,480 minutes, almost one hundred million seconds…You’ll never see the end of it since, as per Zeno of Elea’s paradox; you can endlessly divide the time that keeps you apart from your release. And yet, the biggest paradox: you know that you will see the end of it — that is, if you get out of here alive.

The hell confined in confinement is not the small box (cell) in the bigger box (prison); it is it’s duration within time. The mental tick-tock of subdivision: another hour is one hour less; one less, is one gained — but gained on what? On the time that will be left once you have “served your time”.

Every hour gets you closer to the end of each day, but at the same time draws you away: the remaining two hours become 120 minutes, and those minutes become 7,200 seconds. Time is pressing, but the pressure goes on endlessly.

The hell of the cell is the “static and circular” time, described by Claude Lucas in Suerte, the “gaping time”, the “drawn-out present”… That is, the “pure, repetitive eternity”, says the man known as l’enfermé (the “locked-up one”, as out of his 76 years of existence, he spent 35 behind the bars).

What is time? asks Augustine in a renowned text. “When nobody asks me, I know; but when I must explain, I do not know anymore.

And what is prison? When nobody asks you, you know (the prisoner knows better than anyone); but when you have to explain, the words escape you. The prisoner does not know what he knows — nor even what sort of knowledge would constitute what he knows.

Seated on the bed, elbows on your knees, hands clasped together, you become engrossed in the contemplation of that burn mark on the blistering paint, some twenty centimeters above the small, bolted-down table. A mark of the past, proof that despite all appearances, time is passing by; has passed by, will pass by, would have passed by… But there is a stifling component in time, just as the air is stifling inside the cell during summer: oppressive, sticky, motionless and unremitting air. Between the wall and the face, between the table and the bed, past-present-future weave into one single unit of time; relentless, irremovable.

In the garbage-coated, pie-shaped portion that serves you as prison yard, you stamp on time, you intersperse it with paces and about-turns. The binary measure of time. Time is not to be counted; it is to be scanned — to be stridden across: 22 steps for a one yard loop, one second per step, 163 loops per hour, 6 km per day, 40 km per week, 2,000 km per year. The long walk from present time to nowhere.

Time is not odorless. It smells of gray, of the empty can tossed around by the wind on the concrete slab, of the cleavage of the TV show hostess, of the tepid lasagnas… It has that ferrous taste of blood in the mouth, the texture of that rubber finger rummaging through your anus. The walls of your house are covered with pictures of time: asses, mouths, gaping sexes, endlessly available and unreachable — and the mute cry of that woman, walled-in alive in her counterfeit orgasm. Time does not stop at the gates of the body; it flows in your esophagus, fills your lungs, creeps into your ears, goes back up the stream of your intestines. It invades you and destroys you. The seams of your skin sack are bursting from containing it.

By inflicting the ordeal of time on you, imprisonment manages the tour de force of making your life itself a punishment.

One day, similar to the others, an event comes and pierces the time lid. The collective refusal to go back to the cells after exercise creates an unforeseen and unforeseeablebreach of the repetitive infinity. A step to the side, a spontaneous protest halting the routine: the management is on the ground inquiring about potential complaints — sham negotiations while waiting for the intervention of the security teams. The insurgents are talking about personal belongings that were wrecked during a thorough search of several cells…

The event is miraculous in that motionless time temporarily yields and gives in to becoming. The prisoner seizes the immediate future; he takes it into his own hands (the Latin locution manuscapere gave birth to the beautiful verb emancipate).

The noise coming from police cars maneuvering in the entrance courtyard, on the other side of the building, signals the pending landing of the RoboCops. The following movie has a long-standing pitch. But the experience of it cannot be summarized by police inspection, searches and the punishment of solitary confinement; the agenda is no longer the execution (of the punishment), but the emancipation (of the subject, individual and collective). It is no longer about killing time, but seizing it.

Saying “I”; saying “we”, is to open up to the possible — at the very least, to the possibility itself of new possibilities. It means allowing ourselves to think that the play (life) is not foregone. It means daring to picture that, as a man, “You can always make something out of what you’ve been made into” as Sartre says — and the philosopher adds: “That is the definition I would give (…) of freedom.”

The prisoner unlearns freedom.

You look at your hands, you look at the wall, you look at the window with its wire netting preventing kite exchanges, you look at the book on the table, you look at the graffiti target around the peep hole, painted by one of your predecessors. Wall, hands, book, peep hole, window… You are looking for the fault, the crack in the wall, the interstice, the escape route.

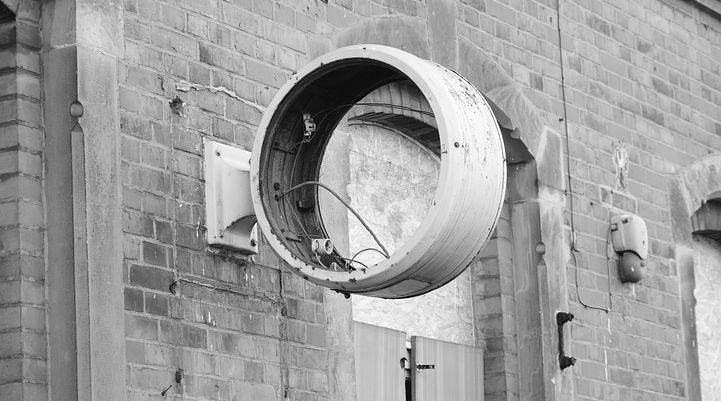

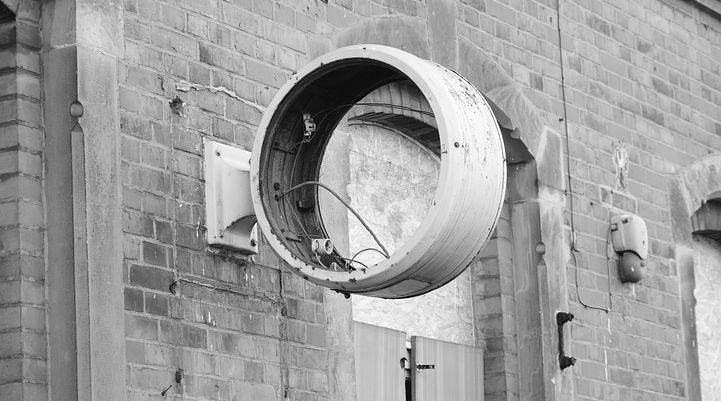

The verb that comes to mind is “to build”. The hand that grabs, assembles, combines, fixes… Something is building from nothing or, say, from a jumble of bars, clamps, boards and rails. But the wall facing you 22 hours a day, as messed up as it is, does not present any grip, nor does it open onto anything. Nothing to build in these 9m² of time-out except shabby, vengeful pipe dreams invading and harassing you.

You should be able to take some sort of decision. Studies? Body building? Religion? You look at that book and you think “but they have decided for me which decisions are possible”, and you say the word “cage”, because you read in the book the poem evoking the “heart bouncing in its cage”. There is nothing wrong with the word “cage” there. The poem was even saying “Imagine the luxury of that life / Try to imagine” — which is what you have tried hard to do while sipping a cup of chicory.

The book cover reads that the author has died from lung cancer at the age of 50. Only a couple of days before his death, he wrote another poem: “There was a time when we thought we had time on our side.”

On the radio, you hear the expression “wall-colored”. Over the past few weeks, you have been finding your complexion a dull gray in the Plexiglas mirror above the sink. Would the color of your skin end up taking on the color of concrete? Color and texture, just like a wall erected between you and the world. Is that the meaning of toughening up?

Your poorly-shaved face has the texture of fresh cement; your eyesight is eroding itself after all the rubbing against the walls. When you do your series of fifty push-ups, the stench of vinegar from the mucked-up concrete floor stings your eyes.

You know a lifer, upstairs, who looks just like a ghost after thirty years of imprisonment. He told you: “Too late, now. No way I’m getting out. I’ll kick the bucket inside, not on the street.” That’s a wall-man, dead in life, for a long time already.

Time does not flow by, does not fly by, does not pass. You see yourself in time as a worm in the world, tiny being progressing in the enormous vastness. You keep track of the days, the months, the years. Eventually there will be an end — but an end to what? Time will remain, and you will remain in time. The enclosure, crossed in one direction, will be crossed in the other. The door will close on your back (like every time), and you will reflect on that moment, the prospect of which has kept you alive all these years. You will reflect on that shapeless bag holding your belongings, next to your feet, you will reflect on the parking lot, and you will check the coins in the pocket of your jacket, and you will go toward the bus stop, and you will wait.

You will leave the prison, but its shadow will never leave you.