Last year, West Virginia contracted with a company, Global Tel Link (GTL), to provide free tablets to prisoners. These kinds of initiatives are rapidly becoming more popular, as states grapple with the legacy of four decades of tough-on-crime policies and renewed public calls for more rehabilitative prisons.

And it sounds great. Until inmates realize the company charges users every time they use the tablets, including 25 cents a page for emails and 3 cents a minute to read e-books. By that calculation, most inmates would end up paying about $15 for each novel or autobiography they attempt to read. To people who have little to no money, that is not a benefit. That is exploitation. The only beneficiary, aside from GTL, is West Virginia, which receives 5% of the profits.

GTL is not alone in profiting off of prisoners. Exploitation of prisoners for profit is cropping up more and more across the criminal justice landscape.

JPay, which is owned by Securus Technologies, charges inmates to make calls, send emails and listen to music and audiobooks. In some states, Edovo (Education Over Obstacles) has charged inmates to rent tablets.

Many prisons now ban in-person visits, then allow companies to charge $12.99 or more for video calls. Prison phone calls can cost up to $3.99 a minute. Prison shoes fall apart within weeks, and replacements are only available from a special catalog. Only sweatshirts are provided for the winter. Meals are nutritionally insufficient and, over time, must be supplemented to maintain good health.

All these necessities — shoes, jackets, phone calls, canned tuna from the commissary — rack up fees well above the market rate on the outside. But they often are not paid for by prisoners, who have little or no means to earn income. They are paid primarily by families who are often among our poorest. This hidden tax drives already vulnerable communities deeper into poverty and hopelessness.

But a charge to read is especially egregious. The great resource in prison is time: the time to think and improve. The best way for prisoners to fill that time is to read. Reading opens up access to instruction across any subject. It teaches job skills. It reminds those left behind that a world exists beyond the cage.

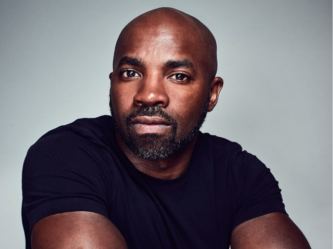

I would know: it happened that way for me. At 18, I was sentenced to life in prison with little hope of parole. For two years, I was depressed and hopeless, with no purpose or goals. Then a fellow lifer introduced me to books. I started reading every day: history, self-help, newspapers, textbooks, biographies.

Reading taught me not only could I make the world a better place, but how to make it a better place: by getting others to read, too.

He and I founded a weekly book club. We got our GEDs. Our Maryland prison did not offer a college degree program, so we researched and wrote a proposal that helped persuade them to start one.

We taught résumé writing and career guidance classes. We helped more than a hundred of our fellow inmates prepare for success in the world beyond the fence. We made dozens of life-long readers. We gave ourselves hope and purpose and the tools for success.

It never would have happened without free books. At one point, my family spent hundreds of dollars over just a few months answering my collect calls. But they didn’t have endless amounts of money to continue that, and I certainly didn’t have money. The idea of spending 3 cents a minute on a book was impossible. I did not have 3 cents.