Explore

Life imprisonment

IN 1981, at the height of the debate on the abolition of the death penalty in France, philosopher Michel Foucault had this warning: “The real divide between criminal justice systems is not between those that include the death penalty and the others; it is between those that allow irreversible sentences and those that don’t.”

Is the death penalty irreversible? Certainly. Is life in prison irreversible? Not necessarily. As the former General Inspector of Prisons, Jean-Marie Delarue, explains “Life imprisonment is a conviction for life, but that does not mean that the sentence will be enforced for the rest of the convict’s life.”(read our interview.). In fact, under criminal law of the signatory countries to the European Convention on Human Rights, a life prisoner should be able to request a reduction of his sentence and hope to get out one day. And yet for around 40 years many countries, including France, have increasingly and overwhelmingly turned to life imprisonment and have made, through successive legislation, the enforcement of this terrible sentence to mean life, something which Larbi Belaïd has painfully experienced (read his life story).

In Europe, only half a dozen countries do not include life imprisonment in their penal codes. Among nations that ignore this sentence, Norway has the least severe penal system in the world. “Norwegians have a clear understanding of the pointlessness of very long sentences; this is because they are not hooked on the seriousness of the crime but are focused on chances for the prisoner to reintegrate, ”explains Jean-Marie Delarue.

But Norway is an exception in a world where many countries lean toward true life imprisonment without parole. In this regard, the United States plays a leading role with over 30,000 prisoners sentenced to stay in jail until their last breath, including 2,500 minors. How can this institutional violence be explained? For Jonathan Simon, professor of law at the University of Berkeley, California (read his interview) “it is the expression of the fear in our society, the same that has helped give birth to the age of mass incarceration”. Other countries on the American continent, such as Honduras, are gradually moving towards the introduction of true life sentences in their legislation (see R.A. Gomez article).

Testimonies of two Italian prisoners, Carmelo Musumeci (see video report) and Marcello Dell’Anna (read his letter), both sentenced to true life imprisonment more than 20 years ago, express the inhumanity and absurdity of very long sentences and, more importantly, of sentences where the prisoner cannot see the end.

France

Brief history by Pome Bernos¶

Life imprisonment, key dates from the French penal code of 1791 to the present day.

Jean-Marie Delarue

General Inspector of confinement Centers from 2008 to 2014 (France)

Jean-Marie Delarue served as the first General Inspector of confinement Centers (official site of the CGLPL) from 2008 to 2014. His legal credentials and vast knowledge of detention conditions in penitentiaries, where “long serving” detainees are held, make him one of the renowned experts in “life sentencing” in France.

In a discourse that is both humane and pragmatic, he denounces the increasing recourse to life-long sentencing by the courts and the laws enacted during the last 40years that make its application increasingly effective.

Jean-Marie Delarue: "Life sentences destroy hope"¶

Prison Insider. In common language, the expression “for life” means “forever.” However, under French law, a life sentence is always carried out with the perspective of a possible release. In this context, what does the penal code mean by prison “for life” or confinement “for life?”¶

Jean-Marie-Delarue. First of all, it is a type of sentencing that penalizes a crime. The penal code lists the types of prison penalties, detentions and imprisonments that can be applied to crimes. It has four types: sentences of 15 years or longer, sentences of 20 years or longer, sentences of 30 years or longer, and lastly, sentences for life. A life sentence means for always. But what needs to be understood is that this life sentence is the maximum sentence given as a penalty for crimes of a most serious nature. It does not mean, as you have already pointed out, that the serving of this sentence will continue for the rest of a convicted person’s life.

There must be the possibility, at some point in time, of attaining a degree of conditional freedom, of eventually being released. But, it is conceded that this possibility has no positive outcome and that, consequently, people remain in prison for the rest of their days.

Regarding this matter, the European Court for Human Rights, which had some difficulty in establishing its doctrine, and which finally carried it out in a 2013 sentence, tells us that when the penal code allows for the imposition of a life sentence, we have the right to ask for an amendment to that sentence. In other words, in legalese talk, the sentence must not be “irreducible.” But if it is not and, if, as a result, the convicted person files an appeal permitted by law and is rejected, that person could very well be imprisoned until death.

Prison Insider. In France, a life sentence is always rendered with a safety period. What does that involve?¶

JMD. A “safety period” is always a part of sentencing for crimes. It is a recent legal measure enacted at the end of 1978 which indicates the continuous balancing of criminal law between two opposites: to give the convicted person a chance to re-integrate, and to apply an appropriately severe sentence. In this continuous balancing, the “safety period” is a type of firming up of the sentence. It is applied in all criminal convictions. This means that, if someone is convicted of a crime, and the length of the sentence is set at between 10 years and life, it is always associated with a period of time during which the sentence cannot be amended: no sentence suspension, no sentence apportioning, no out-of-country placement, no “leave” permission, nor conditional release. In other words, during the safety period, the person is under strict confinement.

For those sentenced to life imprisonment, the “safety period” is set at 22 years and may even extend to 30 years for the most serious crimes. This last measure is recent. It is applied mostly in matters of terrorism. But, even there, it is necessary to balance, because the re-integration of the convicted person must be ensured. So therefore, this “safety period,” determined by the judge at the initial trial, can be amended by the sentencing court for life sentences of 18 years of detention, or of 22 years in cases of recidivism.

Prison Insider. Since 1994, a life sentence is considered to be “real” or “irreducible?” Please explain.¶

JMD. It is a type of sentencing that cannot be altered. But in actual fact, this is more apparent than real because, again, we cannot say that the convicted person cannot ever have his/her sentence amended, in case the “real” sentence would not be in keeping with the statutes of the European Court of Human Rights. This being said, 30 years of safety effectively amounts to 30 years of prison and that is a terrible sentence.

Prison Insider. Jean-Marie Delarue, when you were the Controller of Detention Centres, between 2008 and 2014, you and your team met prisoners who had received very long sentences of 18, 20 and 30 years and sometimes more. What happens to men and women in prison when they are serving such long sentences?¶

JMD. Anyone who has spent time in prison talks about the passage of time. Time can be seen as endless, or going by very quickly. A day can either fly by, or go slowly, but it doesn’t change the way detainees feel. And so, when it’s a sentence for life, and there is nothing to look forward to in this context of time, that, in itself, is the unbearable frustration of detention.

When a person is in prison, there is a need to hang on to some hope, to some possible outlet, and 1-, 5- and 10-year sentences provide this hope. But sentences for life destroy this hope. It has nothing to offer but an endless repetition of days behind bars, without any possibility of change, and that is the absolutely tragic aspect of it as compared to other sentences.

Prison Insider. Do very long sentences, especially life sentences, allow time for perpetrators of murder, rape, and other crimes to appreciate the nature and gravity of their actions?¶

JMD. Naturally, it is very difficult to draw any overall conclusions on this topic, as personalities differ among detainees, but what I can say is, that after a number of years, they give the impression that they understand what they have done. Besides, they cannot help but do otherwise as, when they look at themselves, at the lack of activity and the lack of hope, they are forced to think of what led them to prison. And what they tell us is that it only takes a few years to come to that realization. I can remember someone who was at the 8-year point of incarceration who said to me, “What I did was deplorable, I have to find another way to live.” Will he be released eventually? Difficult to say, but at least he means well. What can one add, when he still has 22 years left to serve? Nothing but suffering. Once, in a prison, I met someone who had been incarcerated for 44 years. What is uppermost after so many years, is not how the criminal becomes aware is of his/her actions, but it is the chance of re-integrating into our lives, the lives of us who have remained outside and to regain the social contacts that were lost after so many years. This is an enormous problem with long sentences.

Prison Insider. Anne-Marie Marchetti wrote in “Perpétuités” (Plon, Terre Humaine, 2001) “…nature and sex are the two most absent elements in the lives of prisoners with long sentences in French prisons.” After 15 years, do you think these words are still true?¶

JMD. I don’t think that penitentiaries have changed very much in their designs, except for the recent models built in Orne and in the north of France which are still unacceptable, with even less access to nature than with the traditional ones. As for a sexual life, it too has not improved. To my knowledge, there are no mixed penitentiaries. So, what A.M Marchetti wrote remains true. I would add that, in many establishments, there are no ordinary friendships. In other words, as a detainee told me, “in prison you never make friends because you can never trust the other person.”

When in prison, it is human interaction that changes. In any case, it is so unique that it cannot be continued on the outside, and so it remains as one of the most painful aspects of long sentences. And I am not talking about the violent interactions that often occur. I talk about people that isolate themselves for 30 years because of the fear generated by the latent violence that is there, in the others, and in themselves.

Prison Insider. What, in your opinion, is most urgent: to improve prison conditions or to shorten sentence time?¶

JMD. I believe we have to play all our cards. Sentence times must be shortened because a long sentence is a cruel way of increasing the protection of society and it reduces the prisoner’s ability to re-integrate.

Prison Insider. At what point during imprisonment do you think that the sentence will “destroy a prisoner’s hope,” to repeat your words, and lose its meaning, if there is any meaning?¶

JMD. I would like the sentencing judge, and the court that renders the sentences, after examining the personality and the progress of each detainee, to have complete freedom to reconsider the safety period and the quantum of sentencing pronounced, so that, from the 8-year point, if necessary, a person can be released if he/she has understood what has happened to him/her.

Prison Insider. So you agree with the recommendations of the European Council which proposes re-examining life sentences at the end of the 8 to 14 years of detention.¶

JMD. In Scandinavia, long sentences are totally inconceivable, and this really made me think. And I believe that we should not think that human nature in Scandinavia is radically different than ours. In fact, if they think, rightly, that very long sentences are not useful, it is because they are not hung up so much on the seriousness of the crime, but rather on the chance that a detainee can be re-integrated into society.

Shortening the time of sentences is crucial, but that is only one component.

The other is the necessity to improve human interaction while in detention, and to establish trust among the detainees. That means that prison administrators must be more than just “guard dogs” -pardon the expression- but must play a greater role in encouraging human interaction.

And thirdly, we have to look at the number, volume and the variety of activities that are offered in prison to help detainees spend their time -sadly, too long- in order to change the way they feel about themselves, to change their lifestyle, to change professions. The more we provide, particularly in penitentiaries, high quality training and activities that engage the whole person, the closer we will get to re-integrate the detainee upon release from prison.

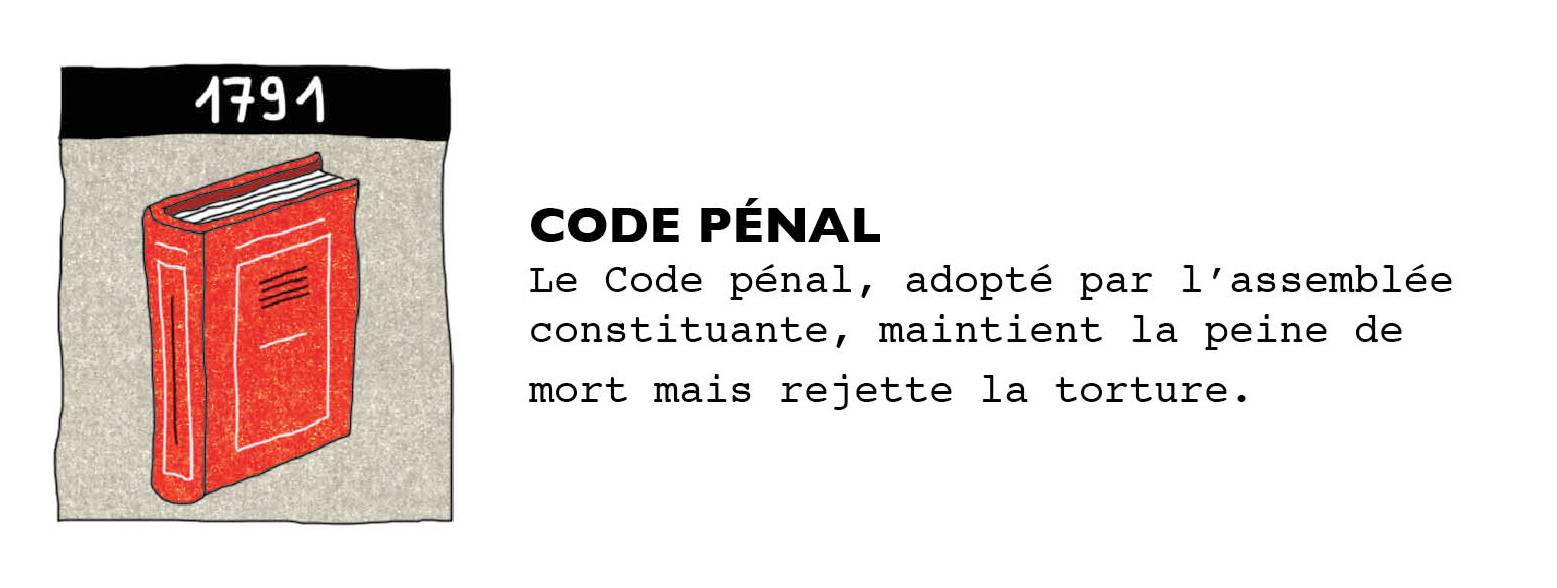

Prison Insider. When one looks at the history of life sentencing in France, we can see that in 1791, the revolutionaries decided to keep the death penalty, but abolish life sentencing. What was the basis of that decision?¶

JMD. It is the notion that a human being is infinitely respectable, and that in case of serious crime, we cannot prolong a sentence indefinitely without harming the dignity of the person. And I believe that is what they thought. So sure, we can say that the death penalty was much worse but, we realized it only 200 years later. The disappearance of the death penalty resulted, in France, in an increase in the number of very long sentences. In 1981, there were 200 very long sentences and today there are about 2,000. The paradox is, we thought we could replace the death penalty with long sentences which do not give the same results, nor -in quotations- “advantages.”

Prison Insider. Last March, Nathalie Kosciusko-Morizet proposed the introduction of an “effective” life sentence, without any possibility of release, which would be imposed on those committing terrorist acts. How do you understand this proposal and do you think that one day, France will implement confinement for life, as in the United States?¶

JMD. For the last fifteen years, we have been in a phase of imposing much tougher sentences. We can see it especially with the number of incarcerations in French prisons which has increased by about 66% in a span of 15 years. The fact that there are more detainees can be explained by the increase in short sentences and the higher number of very long sentences.

** The public does not understand -because we don’t take the time to explain- that life sentencing does not necessarily translate into a sentence that will last until death. The public has never understood, as well, the concept of sentence amendment, because we have never tried to explain the logic behind it.**

For the most part, our fellow citizens think that the convicted person has the same mind-set upon release as when he/she was imprisoned. That means that the public does not believe that imprisonment can in any way help to change people.

Therefore, when the day the legislator - and it will surely happen given the direction this is taking - adopts the principle of an effective sentence, it will mean that the judge and the sentencing court will no longer have a role to play. And for those convicted persons who are no longer able to amend their sentence, as opposed to other convicted persons, the principle of equality between litigants would be invalidated. That will also raise the question of the legality of the sentence which is a constitutional principle. And it will contradict the legal position of the European Court of Human Rights, which says, henceforth: no irreducible sentencing!

Prison Insider. In 2008, with the implementation of security retention in France, have the doors been closed again to one or two additional rounds for those sentenced for life?¶

JMD. Security retention currently consists of keeping in a secure centre, which is not a prison but a specialized place that is more medically oriented than a prison, -in reality, they are not- someone who has committed a particularly serious crime, especially a sexual assault. It is the notorious sexual predator who is never expected to change, or those repeaters who commit rape twice. These are the people who are targeted for security retention, even though criminal recidivism is completely negligible statistically.

Prison Insider. Yet, it is widely publicized by big media as well as by certain politicians who do not hesitate to seize upon it.¶

JMD. In fact, criminal recidivism is often brought to light and greatly exaggerated by the media. And one case can blow all statistics out of proportion. Unfortunately, security retention responds to public opinion which says: “these people should be locked up for life.” And so, confine people in special centres who have committed particularly serious crimes, at the end of their prison sentence and for an indeterminate length of time.

A special regional commission consisting of magistrates is responsible for regularly determining if someone is a dangerous offender, or not. The “dangerousness” of a person, a term which is often used today in our criminal code procedure… I don’t know what it means. And even if some psychiatrists have tried to define it, many others express their reservations on the issue.

Nevertheless, this is the basis of the decision to impose security detention on a person, or not. And, in fact, this security detention is another form of life sentencing, except that it is regularly swept under the judge’s carpet. But if not, it’s a confinement that can last to the end of a person’s life who has already served his/her sentence.

Prison Insider. It is a great responsibility, in the current context, for magistrates and psychiatrists involved, to authorize the release of a rapist or a criminal who has completed his/her sentence. There is also political pressure whenever a prominent criminal is due for release.¶

JMD. We enter dangerous territory when we rely on appearances. No one, no matter who he/she may be, can be reduced to appearances, nor the actions they have committed, as horrible as they may be. Rape is something totally deplorable, but personally, I believe we must accept that people can grow and change. So it is important that the prison provides the means for this growth. As for me, I think this open minded approach is a much better way to deal with recidivism, than by keeping people in prison or in secure detention for the rest of their days. But secure detention, like life sentencing, unfortunately, immediately satisfies public opinion. The public therefore feels it is protected from the actions of people they no longer want in their midst. Thus, by retaining a safety period, life sentencing and long sentences, it will always mean that it takes slow, patient and diligent work to help people grow and change.

As told to Vincent Rouvière¶

At 60 years old, he has spent nearly 38 years inside prisons and detention centres, and knows this universe, which operates at its own pace, like the back of his hand.

Larbi, whose only horizon is a wall¶

FOR LARBI BELAÏD, life outside prison consists of only a few years. Out of the last three decades he has spent barely four of them in the outside world. “For me, the outside world is postcards, or specific periods of time,” this reserved, weather-beaten man says. At 60 years old, he has spent nearly 38 years inside prisons and detention centres, and knows this universe, which operates at its own pace, like the back of his hand.

An animal in captivity.¶

From his childhood, Larbi remembers rows of huts, “between the railway track and the rubbish tip,” in the suburbs of Lyon, and his brothers and sisters, the exact number of whom he struggles to recall, who died, due to the cold and illness. “Five,” he says, hesitantly. He had a childhood marked by “pilfering,” which sent him to a remand home at the age of 13. “It was a real nursery in there,”he laughs. “We already sang songs in uniform there, like convicts.” Faces he came across in adolescencewould often return behind bars.

Well before reaching the age of majority, Larbi began to run away repeatedly, escapades accompanied by burglaries, which would send him to a detention centre. He was just 18 when lengthy terms of imprisonment sealed his future: 12 years’ imprisonment for robbery, then life imprisonment, resulting from a hold-up which went wrong during a year on the run, and in which a postal worker lost his life. The story made the headlines in the 1980s, but Larbi Belaid didn’t want to play down what he did. “I have never been proud of what I did,” he says. “I’m the first to deplore it. When I was up in court, I first of all spoke to his father, and told him that I had never meant his son to die. But, regrets are inappropriate and I am taking responsibility for my actions. I have paid and I will pay.”

“I have always lived in confinement, I am an animal in captivity,” the sixty-year-old remarks. The days started off with the only daily stroll allowed. “The door would open at eight o’clock; we came back an hour later, and then we were in our cells all the time, whereas, today, the rules have changed. We are allowed to walk around twice a day.” He finds refuge in sport and literature.

“I left school when I was 11. When I ended up in prison, I started to read all the classics.” What was the first thing he read? “Robinson Crusoe; I experienced the same solitude as him. I felt good on my own. And literature allowed me to get away, I discovered other worlds.”

Larbi has often assumed the role of the ‘older brother,’ to “look after his mates.” However, his profile as a leader means that he has most often been housed separately.

One week after receiving his sentence to life imprisonment, an escape attempt would leave him with his ribcage impaled upon the metal spikes of the walls of Saint-Paul prison. He pulled through, “miraculously,” at the end of a stay in intensive care, and ended up confined to his cell for 45 days.

“It was as if I had been shut away in a concrete cupboard. You are treated like a wild animal. But being in there didn’t bother me.”

“A long prison term cuts you off from human beings. You find people are cowards, you can’t trust them anymore. People are unreliable, what’s been imposed upon you inside, it’s too ingrained … the spring has broken.”

[audio in French]

From his cell, Larbi has seen those who shared his fate leave, be sentenced to life imprisonment or given long sentences. But he remains, as if nothing had had any effect on the time

Ever since his first jail terms, Larbi has decided to extend the walls separating him from the rest of the world, not desiring any contact with his family. No doubt to bury false hopes slightly in advance.

At the time of his arrest in 1984, after the hold-up which would result in his life sentence, Larbi, was on the run and living with his girlfriend who had recently become pregnant. She tried to keep in contact. “I refused to let her visit all the prisons, but she insisted,” he explains. “I knew that the ties would eventually be cut and I refused to give her any news. She didn’t take it well.” The transfers decided by the prisons would do the rest. “The last time I saw my daughter, she was about to have her third birthday. She wasn’t told about me”, he resumes. He wanted her mother, “a heck of a mother,” to start a new life. As for their daughter, she crossed to the other side of the fence, starting a career in the police, before going into teaching instead.

And he would have another daughter, after meeting someone else, when he was released in 2009. A new interlude of life, interrupted, yet again, by an arrest, three years later.

“We were living beside our lives rather than within them. We tried to do like everybody else, to have a life, but it wasn’t for us.”

From his cell, Larbi has seen those who shared his fate leave, be sentenced to life imprisonment or given long sentences. But he remains, as if nothing had had any effect on the time, at the end of his 15-year sentence. He would have to wait another decade, but “prison will always be there, like a permanent witness. You never leave it.”

Document could not be rendered.

His perception of time passingis stuck within the notion of time he knew when he was in prison, just like how he relates to other people. His first instinct, once he found himself in the open air, was to go to the cemetery in Nancy.

There was no-one there. I felt as if I was back in prison, he says. For me, there is the same connection between prison and death.

He knows that he will never again find his place in this existence. Last June, Larbi was once again sentenced to six years in prison for a hold-up which he has always denied committing. A passage way to the outside which seems to be a dotted line.

Document could not be rendered.

As told to Anne-lise Fantino¶

Italy

Carmelo Musumeci: a special day¶

“OFTEN, it is in the prisoner’s best interests to never have an independent thought and to always agree with his executioner. Yet the prisoner has so many things to convey and to communicate!”

Thus speaks Carmelo Musumeci, aged 57, sentenced to life imprisonment and held for the last 22 years in Spolete prison in Ombrie, central Italy. Self-taught, he has earned a Master in Law from the University of Perugia. It’s there that Daniel Bouy and Mattéo Giouse met him, for Prison Insider, during one of his rare authorised outings from the prison.

The Antigone association

NGO specialised in defending the rights of prisoners

The Antigone association, a NGO specialising in defending the rights of prisoners, is the organisation coordinating with Prison Insider in Italy. Patrizio Gonella, President of the association, answers our questions on life imprisonment, which has been in force in the country for more than 25 years.

The ergastolo ostativo, or “life imprisonment” is a sentence applied to 500 or 600 Italian prisoners out of the 1500 prisoners condemned to life in prison.

“Our fight against life imprisonment”¶

Prison Insider. What justified the establishment in Italy of ergastolo ostativo, or “life imprisonment”, and what are its aims?¶

**Antigone.**The ergastolo ostativo was established following the mafia attacks in the early 1990s, during which the judges Falcone and Borsellino were killed. In reality, the debate surrounding the conditions of imprisonment and access to other measures had begun before these events. The “Gozzini” law, adopted in 1986, envisaged that all prisoners (including those with life sentences and regardless of the nature of their crimes) who demonstrated good behaviour might be able to benefit from alternative measures, whether at the beginning of their sentence or after the completion of part of their sentence. This enabled those imprisoned for life to more quickly attain day parole and ultimately parole. It was a very progressive law which had been passed in a context where we thought that we had eradicated terrorism.

Prior to this, in the 1970s and 1980s, we had put in place numerous limits with regards to lightening sentences in reaction to the armed terrorist combat.

The 1986 Gozzini law had been called into question several times following its promulgation by a number of people who judged it to be too permissive. The Mafia attacks in 1991 signalled the start of a difficult period for Italy with the end of the first Republic and a series of investigations into the corruption of the Italian political class. It was in this context that constitutional reform was undertaken. This reform envisaged more restrictive guidelines for the granting of grace or amnesty; it is now necessary to have the agreement of two-thirds of MPs to do so, whereas before 51% of them sufficed. By demonstrating a form of intransigence, the political class, wracked by crisis, tried to conserve a trustworthy reputation.

In the same vein, the introduction of two legal measures rendered harsh Italian penitentiary regulations more severe:

The article 41 A of the law concerning the structuring of the penitentiary system envisaged the application of a penitentiary regime particularly harsh towards prisoners whose convictions were related to Mafia activity. The application of this regime was to be determined on a case by case basis by ministerial decree and set out for the isolation of a prisoner for a short period.

In reality, however, the ministry could renew the regime several times. Hence there are today prisoners who have been under such a harsh penitentiary regime since 1991! There are currently 600 to 700 people under the regime in Italy. In the vast majority of cases, these prisoners have been convicted of Mafia-related crimes; very few are serving sentences for a crime linked to international terrorism. When we talk about Mafia-related crime, we are talking about all Italian Mafias: the Sicilian Mafia (Cosa Nostra), the Napolitan Mafia (Camorra), the Calabrese Mafia (’Ndrangheta) and the Puglian Mafia (Sacra Corona Unita).

The article 41 A of the law concerning the structuring of the penitentiary system envisages that all of those who have been convicted of organized crimes (offenses often linked to Mafia activity such as armed robbery, kidnap, extortion, with international terrorism added afterwards) cannot benefit from alternative measures unless they collaborate with the justice system, even if they demonstrate irreproachable behaviour. Yet certain prisoners cannot collaborate or do not wish to do so. Sometimes, their collaboration is not judged to be useful. In this way, these people are condemned to spend the rest of their lives in prison.

This is what we call ergastolo ostativo, or “life imprisonment,” a sentence applied to 500 or 600 Italian prisoners out of 1500 prisoners condemned to life in prison.

This situation has created the problem of “unrequired collaboration,” which concerns those prisoners who never had or who no longer have useful information. In such cases, an exemption from the article 41 A is theoretically possible. It’s this exemption which Carmelo Musumeci, imprisoned since 1992, was able to benefit from: he had no more information to provide concerning the criminal group of which he had been part because it had been entirely shut down1. His is the first case which could open the door to a precedent for instances of unrequired collaboration.

Prison Insider. What is the nature of the debate currently surrounding life imprisonment in Italy?¶

Antigone. At the moment, there is no debate. The last time that a law for the abolition of all forms of life imprisonment was proposed was in 1998. However, there is an ongoing debate about the reform of penitentiary regulations which could have repercussions for the question of “ergastolo ostativo.” In 2013, Italy was condemned by the European Court of Human Rights on the grounds of “inhuman and degrading conditions of detention” owing to overpopulation in Italian prisons (decision Torreggiani, 2013). As a result, Italy was forced to implement measures in order to reduce the number of prisoners as well as to improve the conditions of their detention and guarantee their rights. As such, the government produced a reform of penitentiary regulations which includes 12 articles covering a range of issues such as work, sexuality, minors, foreigners and religious rights…

The Antigone association has participated in this process by providing suggestions for its improvement. Hence, the government has taken into account the propositions of certain academics involved in the development of the reform and has proposed the abolition of the article 41A. Such a provision would have given judges the power to grant adjustments to the sentences of those convicted for association with criminals and implied the disappearance of “ergastolo ostativo.” Yet once the text reached Parliament, the reactions were negative. The bill was thus modified to its detriment: it maintained the ban on adjustments to sentences for people convicted for mafia-related crime and terrorism. The reform is currently being debated in the Senate, but given that governmental parties benefit from only a weak majority it is unsure whether it will be passed.

Prison Insider.What are the aims, the activities and the positioning of the Antigone organisation?¶

The Antigone association has existed for the last 25 years. Its history, however, dates back to the 1980s during the period of terror when it took the form of a review dedicated to criticising the state of emergency and the authoritarian evolutions of the penal system.

Currently, our activities consist in developing political propositions and cultural initiatives, as well as engaging in lobbying Parliament in order to obtain more guarantees in terms of the respect of human rights in penal and penitentiary systems. On the one hand, we are engaged with all elements of procedure, fundamental rights, penitentiary regulations at a national and international level and, in particular, at the European level. On the other hand, we are in the field thanks to our 12 regional satellites which work around four principal axes:

- A national observatory for the conditions of detention which has existed since 1998 and works alongside the OIP (International Prison Observatory), which is based in Lyon. The members of our observatory, who number around 60, are allowed to visit Italian prisons, those for young people and adults, in order to observe them. For the last few years, we have also had permission to film in these prisons. We present on an annual basis a report on the state of Italian prisons 2.

- A committee of “civic defence of people deprived of freedom” composed of young lawyers. We are contacted between 20 and 30 times per week from all over Italy. We deal with these demands, we respond and try to help where possible, even going as far as legal action if it is necessary. We work on a national and international scale, sometimes taking pleas to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). Of course, we only deal with problems regarding the undertaking of prison sentences, rather than at the moment of trial.

- Judicial information support is made available in certain Italian prisons where prisoners can access legal and medical aid, an activity which is often undertaken in cooperation with universities.

- National and international research efforts, mainly in the framework of the European Prison Observatory, which is composed of eight collaborators.

We have a very small team of four people which is charged with the organisation of all of these activities, but our actions are undertaken by tens of volunteers who have gotten involved with the organisation over the course of time. We have lots of people asking to volunteer, and we cannot always accommodate them. The association has 300 members. It is subsidised by European Union funding and private funding.

See our interview with Carmelo Musumeci ↩

Antigone is one of the associations reporting to Prison Insider. Read the annual report on Italy, 2015 ↩

As told to Agnese Pignataro¶

“My prison is a tomb for the buried alive"

The first letter of Marcello Dell Anna¶

MARCELLO DELL’ANNA has spent most of his life in prison. He was sentenced to ergastolo ostativo (life imprisonment prison without the possibility of parole) when he was 23, when he was one of the leaders of la Sacra Corona Unita (an Italian Mafia based in the Puglia region).

Today, he is 49: he is held in the Badu ’e Carros à Nuoro prison in Sardinia. He was willing to enter into an exchange of letters with the Swiss journalist Laurence Bolomey as well as the regular publication of his letters on the Prison Insider website..

Dear Laurence,

It was with great pleasure that I received your letter. I hope that the delay in replying has not posed a problem. I hope you don’t mind me speaking in a familiar tone, not out of lack of respect or concern to do with engaging in a confidential relationship with you, but simply because I feel able to speak more freely, more directly. I can adopt a more formal tone if you wish.

I am aware of your training in journalism and am happy to enter into this correspondence and to undertake this project in order to give a voice to those who, in this sort of place, do not have one. Most importantly, I hope to raise awareness of a current form of sentencing in Italy which is somewhat absurd: l’ergastolo ostativo. Pope François calls it “the hidden death penalty.”

Before going on, let me introduce myself. I was born in Nardo, a city in the province of Lecce in the Salento region, south of Puglia. My current home is called “prison.” I have spent 28 of my 49 years alive here. I have been detained constantly for the last 24 years. I am doing out a life sentence: not “life” in the popular sense, but in the sense of ostativa.

I am married and I have a 28-year-old son. I am a prisoner who demonstrates a clear interest for studying and a passion for writing. During these years in prison, I have received several awards and prizes, as well as merit awards and professional qualifications at further education and university level in Law, which I gained in 2012 with the highest grade, for which I received a distinction from the Spoleto Prison administration. I have written some books and several judicial documents.

Often I feel that, ultimately, when you are condemned to life imprisonment, the fact of becoming a different, better person, is only of a secondary importance, because you remain condemned to never leave. Today, it must be said, for people like us, those serving life prisoners of the “ostativa” kind, prison is a tomb for the living.

You have the feeling that you are some kind of human residue who lives outside of the natural cycle of life. L’ergastolo ostativo conditions us, dehumanizes us, changes us, and breaks us down physically and mentally. Of course, we no longer wear the striped garments or the white straitjacket, we wear nothing more than the number on our caps, but the reality is nonetheless the same, unfortunately. Each one of us is a number, sometimes just a file.

If you enter into the lair of this infernal sentence, you will perceive a sad, unreal atmosphere in which we, “ostativi” prisoners, move like robots. The rhythms, habits, limits of existence have been altered. All is shaped by this reality which is lights years from normal daily existence.

Ostativa, life imprisonment, changes everything. Your being, your smile, your thoughts, your way of walking, loving, believing, hoping or dreaming… Ergastolo ostativo is responsible for the human and social breakdown of men.

This sentence represents a form of experimentation of regression, a daily reality full of desolation. It is a simulacrum of life which inflicts psychological wounds. It often incites a return to crime. Almost always, we begin to fade away.

The lack of hope and the awareness of one’s death in prison become the painful roots of mental breakdown, of an aging of the emotions. We can thus imagine without difficulty the state of mind of those people who know they will indeed one day cross the prison gate, but will do so feet first. We see everything around us collapse. We feel, vividly, this collapse, anxiety, a hole in our existence.And to boot, there’s our remorse. And our remorse dominates.

Behind the bars and the cement, we, the ergastolani ostativi, no longer feel ourselves to be human.

Prison takes shape as the space of our total destruction. The things which happen to us, feelings, emotions, fears and hopes, hatred and love, form bizarre outlines in our non-reality, which become alarm signals. Each one of us lives as a hunted man. Personally, I feel more than anything that I have been thrown back, vomited out by society.

** Now, I am somebody else. Altered, deformed, assaulted in my very essence, I am now a body which has grown old too quickly, an anonymous face, eyes without sparkle, facing the nothingness before me.**

And we are too few to react, to be able to resist and beat this monster. Many give in.

It must be said that in each penitentiary system there is a fundamental contradiction: on the one hand, there is a hope of teaching prisoners a lifestyle which will enable them to live in an appropriate way in the free world. On the other, these same prisoners are bound to live for their whole lives in a prison which is the antithesis of the free world. The fact of living this sentence creates a particular sense of self, a sense of a person deprived of all of their rights. We find ourselves in a situation of an absence of self-determination.

And yet, some of us, after decades of imprisonment, after having died through them, after having indemnified in some way society through the harshness of their conviction, are aware of being new people, born out of their own ashes, who discover a belief in their own value of being human. The Constitution seemingly believes in this renaissance but, in fact, this is not the case. For our Institutions, it seems that we must stay the same forever, die guilty of transgression already paid for through the loss of our youth, of our ripe age… paid for through our lives and those of our loved ones.

Everybody can change and a democratic State should always give a second chance on the basis of objective facts relating to a clear path of rehabilitation. Such change many of us have achieved because we have had the courage to question who we are, by distancing ourselves firmly from the world of crime, because we have reached a level of maturity which enables us to not forget a single moment of the pain that we have inflicted upon our victims through our actions.

To conclude, I would like to say that we cannot deny the freedom of a man on the sole basis of an act which often took place decades ago. We cannot accept it by hiding behind a blackmail which rests upon a shameful obligation to provide information. Society has the right to demand the reintegration of people who have changed, better individuals who respect social rules and regulations, rather than the reformed who have bought their freedom in exchange for confessions, often dubious but well presented, and who will remain, fundamentally, criminals, dangerous assassins with all that this implies for society.

I ground this argument in my own experience, in the evolution and metamorphosis of a “new person” who no longer thinks like an ostativo prisoner. And to you, citizens of Switzerland, of France, of Europe, to you, lawyers and politicians, I would like to address the following question, first posed by a famous lawyer: How is it possible that we tolerate a system without which prisoners are denied human rights? What form of humanity will you leave your children if you have to explain that in Italy there is a monster, ergastolo ostativo, that swallows up those who have erred, which forces those it imprisons to live out a ten-fold sentence? With what heart will you say to those who will take over in that country, a cradle of civilisation and rights, that there exists a system which entraps live human beings and which strips them of their dignity as men?

Dear Laurence, I hope my replies to your questions are exhaustive and understandable. I have written what I feel in my heart because from there come authentic observations from which I suffer bodily every day.

I would much appreciate hearing your opinion on the matter. I look forward to news from you.

Yours sincerely.

###Marcello Dell’Anna

Honduras

Life sentencing : a criminal setback in Honduras¶

TOUGHENING penalties, getting rid of precautionary measures for 21 crimes including murder, and implementing life sentencing have been some of the social deterrent activities over the last four years through which the government of Honduras has sought to reduce the crimes that have made it one of the warless nations with the highest violent death rates in the world.

Based on data from the National Statistics Institute (in Spanish, Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas orINE), Honduras has a population of 8.7 million inhabitants. Out of that population, 16 thousand are in prison, according to the National Penitentiary Institute (Instituto Nacional Penitenciario or INP).

Congressman Tomás Zambrano, president of the legislature’s Security Commission, is a proponent and defender of life sentencing, believing it is a necessity.

“If a criminal abducts and kills someone, upon being found guilty in a court of law, that person must be sentenced to prison for life, and the same sentence should also be applied in cases of aggravated extortion. These are reforms we have already completed.”

For former sentencing judge, criminal law university professor, and attorney Ramón Barrios, life sentencing would not achieve the objective for sending a person to prison. “Sending someone to prison who has been sentenced to life for any crime goes against one of the main tenets of prisons, which is to reform individuals who have been convicted, so they can be reintegrated into society.”

Article 87 of the Constitution of Honduras states: “Prisons are established for the safety and defence of society. What they provide is rehabilitation of the person incarcerated and his/her preparation for employment.”

Reform¶

Before 1997 the Constitution of Honduras did not address the application of life sentencing. However, it was at the root of a reform created that year, in response to the abduction and murder of the son of a well-known politician and ex-president of Honduras (Ricardo Maduro, 2002-2006). The National Congress amended Article 97 of the Constitution, which stated, “No one shall be condemned to life sentences,” to, “The penalty of life imprisonment is hereby established.”

Since that time, a number of sentences have been handed down by judges that, due to the sum of the crimes, have condemned a person to be imprisoned for the rest of his or her life. For Joaquín Mejía, Doctor of Human Rights, with life sentencing, “there is an attempt to normalize a theory that cannot be found as such in the Penal Code, but has been applied in practice over the past two decades.”

Contradiction¶

Although the Constitution of the Republic of Honduras now establishes life sentencing, there is a contradiction with the Penal Code currently in effect, which in Articles 35 and 36 states that “accumulated sentences shall not exceed thirty years,” and, “in the case that the crime carries with it the penalty of a life sentence, 20 to 30 years of imprisonment shall be applied.”

“No one can be in prison for life,” says Barrios. Congressman Zambrano, member of the ruling National Party (Partido Nacional), says that they have begun to institutionalize a new Penal Code because of this type of ambiguity. “We are seeking to pass a new one to erase all of those contradictions with the current law.” Despite this “ambiguity” as Zambrano calls it, during the last three years, Congress has approved reforms for extending sentences in Articles 116, 221, and 322 in the Criminal Law for crimes of assassination (the murder of presidents in the three branches of the government, justice workers, members of National Security Council and Deputies), the sentences for which go from 40 years to lifetime imprisonment.

As an example, three Hondurans have been sentenced to life in prison in the Marco Aurelio Soto National Maximum Security Prison since June of 2014: brothers Osman Fernando and Edgar Francisco Osorio Arguijo, and Marvin Alonso Gómez, sentenced for aggravated kidnapping in the case of journalist Alfredo Villatoro, abducted on May 9, 2012 and found dead on May 15 of the same year. These three Honduran men joined a prison population numbering approximately 16 thousand inmates, even though the 24 prisons of Honduras only have a capacity for 8 thousand, according to information from the INP.

This creates a level of overcrowding of one hundred percent, which forces those imprisoned to serve their sentences under subhuman conditions that violate human rights.

“I am against life sentencing due to the poor research behind it and poor prison conditions,” said Judge Mildred López, who supports her position by adding, “if a person is condemned to live their entire life in prison, there won’t be any motivation to change his or her behaviour, and the constitutional objective for sentencing is lost. What we will have is someone more resentful towards society, and a burden on the State.”

The Honduran penitentiary system is in an uncomfortable situation where they have lost upwards of 600 inmate lives to tragic events since 2002 due to riots, gang confrontations, and fires (361 deaths on February 14, 2012 due to a fire at the National Penitentiary in Comayagua, 100 kilometres (62 miles) from the capital of Tegucigalpa, according to data from the National Human Rights Commission of Honduras).

Zambrano explains that in the new criminal code they will establish a revisable life sentence following the inmate’s first 30 years served in prison, “but it is necessary that the maximum sentence is served as a consequence of criminal acts,” he asserted.

However, this explanation does not bring relief to the issue. Mejía insists this causes, “a setback in matters of crime, because it casts aside the right of the people to be rehabilitated. Therefore, when a criminal code establishes life sentencing, it is openly violating the basic principle of liberal criminal law.”

Opposing congressman, Bartolo Fuentes, agrees with life sentencing, but as an alternative to the death sentence, which at this time has been rejected by the country.

In 2015 Honduras registered 14 murders per day, a mortality rate of 60 for each 100 thousand inhabitants, according to the most recent report from the National Autonomous University of Honduras Violence Observatory (OV-UNAH), which is 25.6 homicides less than in 2012.

For Julieta Castellanos, UNAH president, there is no way to demonstrate a relationship between sentence length and a decrease in crime, much less an inhibiting effect on homicides. However, she is in favour of life sentencing, “because it denies freedom to criminals who can continue causing damage to society,” she explained.

Former sentencing judge Ramón Barrios, reminds us that, “every time there has been a rise in homicides, murder, and rape, the only measure the State has taken as a response has been to increase sentences, but historically we see that, as a society, we have become more violent, and crimes outside of prison have continued.”

But Congressman Zambrano firmly believes that implementing life sentencing is a real dissuasive measure to stop the wave of violence. “When a criminal commits heinous crimes, the weight of the law must come down with full force, accompanied by harsh sentences. These types of sentencing exist in developed countries, and we as a government have an obligation to implement them,” he said.

Mejíaposits that promoting life sentencing must be considered “penal populism” because they use the fear generated by violence to adopt measures with immediate results in elections, sending a message to the population that they are a government that is tough on crime, and that’s why they should vote for them. “That doesn’t help. Other measures are needed, like improving the living conditions of the population,” he stated.

Repercussions¶

Honduras directly contributes to overcrowding through a policy of massive incarceration, which sends an average of 20 people to jail every day, according to the National Committee for the Prevention of Torture (Comité Nacional de Prevención contra la Tortura or CONAPREV).

“Prison is not a rehabilitation centre where a person acquires habits for reintegrating into society; it is the complete opposite. People acquire new techniques for committing crimes and, far from reforming, they come out with more resentment. A prison in Honduras is synonymous with a school for crime,” assured Barrios.

“At this point in time, when in theory there is no life sentencing, and we have seen multiple tragedies in our prisons with the effect of terrible overcrowding, we must think of what it will be like when it actually becomes legal,” Mejía forewarned, continuing, “other measures with a negative impact have also been adopted, like the excessive use of pre-trial detention and ignoring alternatives to prison for 21 different crimes. This is the context in which life sentencing is being attempted.”

Facts

- The daily food budget for an inmate is USD$1.35.

- 223 people in detention have been sentenced to more than 41 years in prison by the Honduran courts. (Source: Penitentiary Audit Program (Programa de Auditoría Penitenciaria))

- Out of 16 thousand inmates, only 7 thousand have received final judgement.(Source: Secretary of Human Rights, Justice, Governance, and Decentralization (Secretaría de DerechosHumanos, Justicia, Gobernación y Descentralización))

Rommel Alexander Gómez¶

United States of America

THE UNITED STATES are one of the very few countries that allow life imprisonment without parole, or in other words, they can imprison men, women and juveniles until they die. In 2012, 49,081 of the prisoners were serving life terms without parole. Among them, 2,500 were juveniles. The United States are the only country in the world that sentence adolescents to life without parole.

Jonathan Simon is a professor of Law at UC Berkeley and director of the Center for the Study of Law & Society.** He answered to Prison Insider’s questions.**

49,081

prisoners serving life terms without parole¶

It is a manifestation of the fear present in our society, the same that also gave rise to the era of mass incarceration. It is a result of the generation that experienced a sharp increase in crime rates in the 60s and 70s of the past century

Prison Insider. How many prisoners are serving a life term on American soil?¶

Jonathan Simon. Before answering this question, we need to understand the notion of “mass incarceration”, which I will elaborate on with the following three points.

First, incarceration rates have increased dramatically over the past forty years: it went from 100 prisoners per 100,000 American citizens in 1970 to 440 prisoners at the beginning of the 21st century. Today, we reach 700 prisoners per 100,000 American citizens.

Second, these imprisonments affect mainly groups already marginalized in American society, in particular Afro-Americans for whom incarceration rates have always been higher than for Whites or Latinos. According to Harvard sociologist Bruce Western, one third of Afro-Americans born after 1970 serve a prison sentence at some point in life. This proportion doubles if you consider only those who haven’t finished a secondary education. More than 90% of individuals convicted to a very lengthy prison term belong to the poorest social classes.

Finally, there is a historical dimension to this: while half a century ago jurisdiction considered the committed crime in the context of the criminal records of an individual, these records do not affect the duration of the penalty anymore in the era of mass incarceration. We call this a categorical imprisonment. With the categorical imprisonment, the average time in prison got prolonged too. For example, in 1970, homicide was penalized with 10 to 15 years in prison. Nowadays, prison sentences for homicide range from 30 to 40 years or more. This prolongation plays a crucial role in the question of life imprisonment.

Now, coming back to your question, according to the NGO “The Sentencing Project”, there were 159,520 prisoners in 2012 on American soil that were serving a life sentence. 49,081 of those were not eligible for conditional parole. Among them are three hundred women, with men in the overwhelming majority of them.

Prison Insider. Does this mean there are different types of life sentences?¶

JS. We can distinguish three types of life sentences.

The life without parole does not provide any possibility to get out of prison except if a governor pardons somebody.

Another type is life sentence without “indication” for the possibility of early release from prison. Some states simply eliminated this mechanism, like Florida, which might restore it in case the legislators passed a new law. This would allow prisoners jailed for life to find hope again.

Finally, the third category consists of life sentence with the possibility of release from prison, “life with parole”. But prisoners on life with parole hardly ever get parole because of administrative powers. These powers are controlled by political forces that build their credibility by defending the most repressive measures against criminality.

Prison Insider. The European Human Rights Council explains that in order for a life sentence not to be considered as torture, it must come with the perspective of release, even if far-off and under very strict conditions…¶

JS. Indeed, the most important factor for a jail sentence to not be degrading is hope. If multiple people held in prison do not have any hope of early release, the global psychology of the prison is altered and gangs are born. If a prisoner does not have any possibility to get out of prison some day, there is no reason for them to behave well. Without a conceivable future, they will want to maximize the power and pleasure even in prison itself.

As soon as more than 10 to 15% of prisoners are sentenced life without parole within the same jail, the entire dynamic changes.

Prisoners who don’t have anything to lose and nothing to hope for are very dangerous. Oftentimes prison guards can feel it… and they send them more often to solitary confinement. Life without parole surely has a multitude of effects on the individual, but it also has an enormous moral and cultural impact on American prisons.

Prison Insider. What happens to these prisoners psychologically? Is there an increase in cases of depression or decompensation?¶

JS. Estimations are that about 40% of the prisoners suffer from a significant mental illness. However, we have good reason to believe that the actual numbers are even higher as the prisons are overcrowded and adequate psychiatric care cannot be provided to the entire prison population. Hence, it is very likely that 20 to 30% of the mentally ill prisoners are not diagnosed. Prisoners on life, representing about 10% of the prison population in US, make for 25 to 30% of the total of mental illnesses. This subgroup is thus particularly affected. A large majority of people become sick, psychologically, during their jail time because of the length of punishment, which gives rise to a combination of boredom, fear and stress. Prison poses a threatening environment in which actual violent incidents are rare but possible violent eruptions permanently felt.

Just recently, the occupancy rate of prisons in California was between 200 and 300%. The overpopulation and lack of privacy contributed to the exacerbation of mental illnesses and the risk of suicides. Compared to other countries, people in US prisons commit suicide twice as often.

Prison Insider. What does daily life for a prisoner on a life sentence look like?¶

JS. In the US, the essential rules that link the states in terms of prison politics are constitutional decisions of the Supreme Court. These decisions are based on general principles that have only limited impact on the actual jurisdiction in each state. There are thus vast differences between the states with respect to access to family, visits, education programs, the level of overpopulation, etc. What is for certain is that prisoners who are in jail forever have hardly any access to rehabilitation programs.

Prison Insider. How much does an inmate for life cost?¶

JS. Several bills aim for replacing capital punishment with life sentence on the pretext that the latter costs less. This is true to the extent that the legal costs entailed by the execution of a human being are high. However, keeping a person in prison for the rest of their life causes significant costs too, in particular with respect to health. This is particularly important as the prison population ages and time in prison increases. Many people think that prisoners work and exercise all day long… In reality though, they lead a sedentary life, are overweight, and suffer from illnesses like diabetes, hepatitis, cancer, AIDS and cardiovascular diseases. As a result, the average annual cost per prisoner ranges from $40,000 to $50,000. These costs increase further to between $100,000 and $200,000 dollars as the inmates get 50, 60 or 70 years old (the majority of them will live longer).

Again, let’s look at the example of California: in 2012, one third of the prisoners will be at least 55 years old and health-related costs will vary between 2 and 3 billion dollars.

Prison Insider. If I understand correctly, certain opponents of the death penalty propose to replace it with life sentence as the worst punishment!¶

JS. Yes, this is the ultimate irony!

Death penalty and life sentence are two essential elements that differentiate the penal politics of the states. Traditionally, those without death penalty neither had life sentence because they didn’t have a maximal level of punishment. In these states, all criminals have the possibility for parole some point in their sentence. Recently however many of these states adopted life sentence out of fear to appear too lenient compared to others. From another perspective, more and more states embracing death penalty, such as Texas, also adopt life sentence.

At the end of the day, I think that the increase in life sentences is more due to political than to economic reasons. Even if, as we already elaborated, it has a big financial impact. At the same time, this is also what leaves us with hope for change in the current period of reforms in the US. The crisis of 2008, among others, significantly weakened the states at the budgetary level. But the states also are the biggest payers of the expenses related to these long sentences. In other words, as explained earlier, the older prisoners are very expensive while being less likely to recidivate. Thus, these people are the most interesting to release if the objective is to reduce the costs for states without imposing too big of a risk onto the public.

Prison Insider. The life sentences imposed on minors are particularly shocking. Are they called into question?¶

JS. Since Graham vs Florida (2010) and Miller vs Alabama (2012), the Supreme Court has decided that juveniles who have not committed any homicide should not be sentenced for life. The reason is the lack of cognitive and emotional maturity. However, if an adolescent of 17 years violates and kills somebody in a particularly hateful way, the judge still has the possibility to send them to jail for life. Currently about 2’500 minors are in prison for life without parole. But the recent decisions of the court should allow changing the sentences of about 2’000 of these minors.

Prison Insider. How does the American society make sense of lifelong incarceration?¶

JS. It is a manifestation of the fear present in our society, the same that also gave rise to the era of mass incarceration. It is a result of the generation that experienced a sharp increase in crime rates in the 60s and 70s of the past century.

The idea behind life sentence is to see these prisoners as zombies that are indifferent to the violence of their crimes and the harshness of a punishment, and resistant to any effort to change. This is a vision of the human being that is incompatible with their dignity.

The good news is that the new generation of millennials, born around the beginning of the 21st century, have a very different perspective. They grew up in a world in which crime rates have decreased. At the same time, they have to face grave economic and environmental threats. Ultimately, they do not consider prison as an effective tool. My son, who is rather for Bernie Sanders, recently went to an event of Hillary Clinton. One of her slogans was: “the era of mass incarceration has to come to an end.” This was still unthinkable when her husband was president of the country. Thus, this is rather positive… I think that it is very important to get rid of the death penalty. Once we succeeded in doing so, we will also be able to eliminate life sentence.

As told to Alice Gadamour¶

Jonathan Simon

Professor of Law

Jonathan Simon is a professor of Law at UC Berkeley and director of the Center for the Study of Law & Society. He has authored several renowned books on criminal justice, among others “Mass Incarceration on Trial”.