I FOUND MYSELF with these prisoners who had escaped being kidnapped by Franklin Masacre, the pran of the General Penitentiary of Venezuela. The prisoners arrived by themselves to the 26 of July Prison, which is almost next to PGV, where they turned themselves in to the Ministry of Prisons’ authorities.

Officials from the Ministry of Prisons gave me access on two occasions, the 17th and 18th November, 2016. On the first occasion, I could see the operation the Ministry was implementing to deal with the prisoners during this abnormal situation. The first thing was to check their physical state and health in the completely insufficient prison infirmary, since four of the rooms were filled with prisoners, crowded together but being treated by the medical personnel.

As there weren’t sufficient beds, they had to sleep on the floor. In the rooms, as well as the reception and the hallways. It was suspected that many of them were sick with tuberculosis.

This was of greatest importance, and I was most interested by this, then it gave me an idea of how life was for those who were in PGV. Nevertheless, access was limited, I only had ten minutes in the infirmary. The Ministry wanted to show the whole operation, which included identification, collation of the data collected by SAIME, on each of the prisoners, with ministerial information, to classify the escapees.

The next day, I was permitted to witness a transfer of 400 prisoners to other penal institutions closer to the jurisdiction in which they had committed their crimes and where they had open cases. They were going to be moved in six buses, guarded by the National Guard.

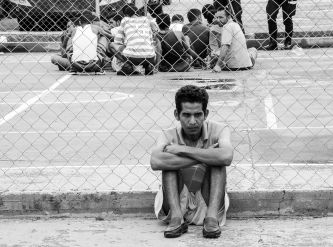

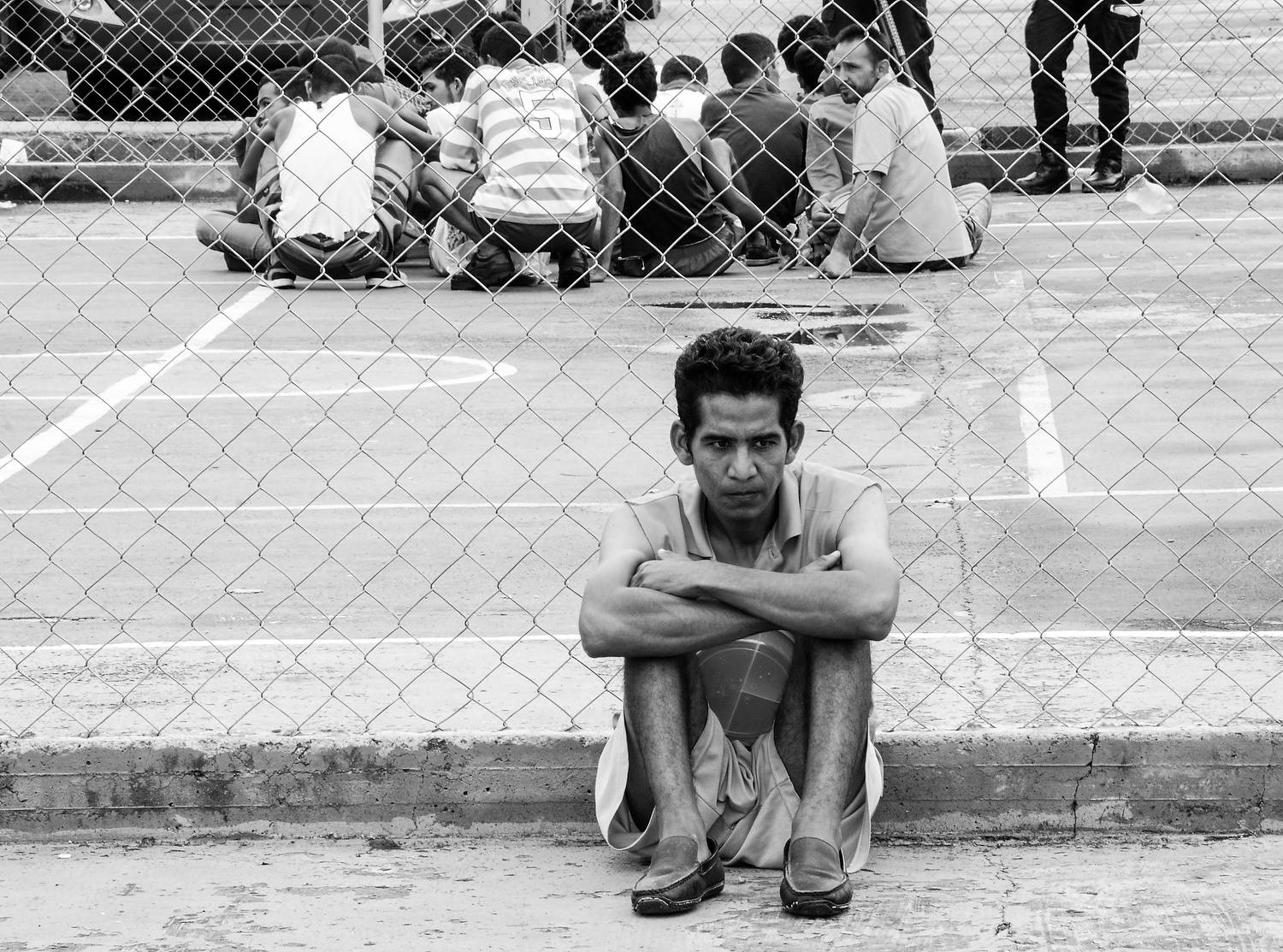

When I entered, they were almost all sitting on the ground, in the prison courtyard, waiting on the National Guard inspection and listening to the instructions from ministry officials about their move.

Besides the photographers from the ministry, I was the only photographer there.

I started taking pictures, not knowing how long they would allow me to. I sensed that it wouldn’t be long, so with my two cameras I took pictures of everything that I could see.

What immediately caught my attention was how young they all were; although they were malnourished and skinny, you could clearly see that many of them were in their twenties. That impacted me a lot, there were more young people than I expected to see.

From the first moment, I realised their state of malnutrition, and I could see the tension in their face, because they did not know what was going to happen, nor where they were being moved to. They tried very hard to listen, but they were inattentive, trying to look at every side, maybe looking for familiar faces. They were sitting on the floor, with handcuffs pairing them with another prisoner.

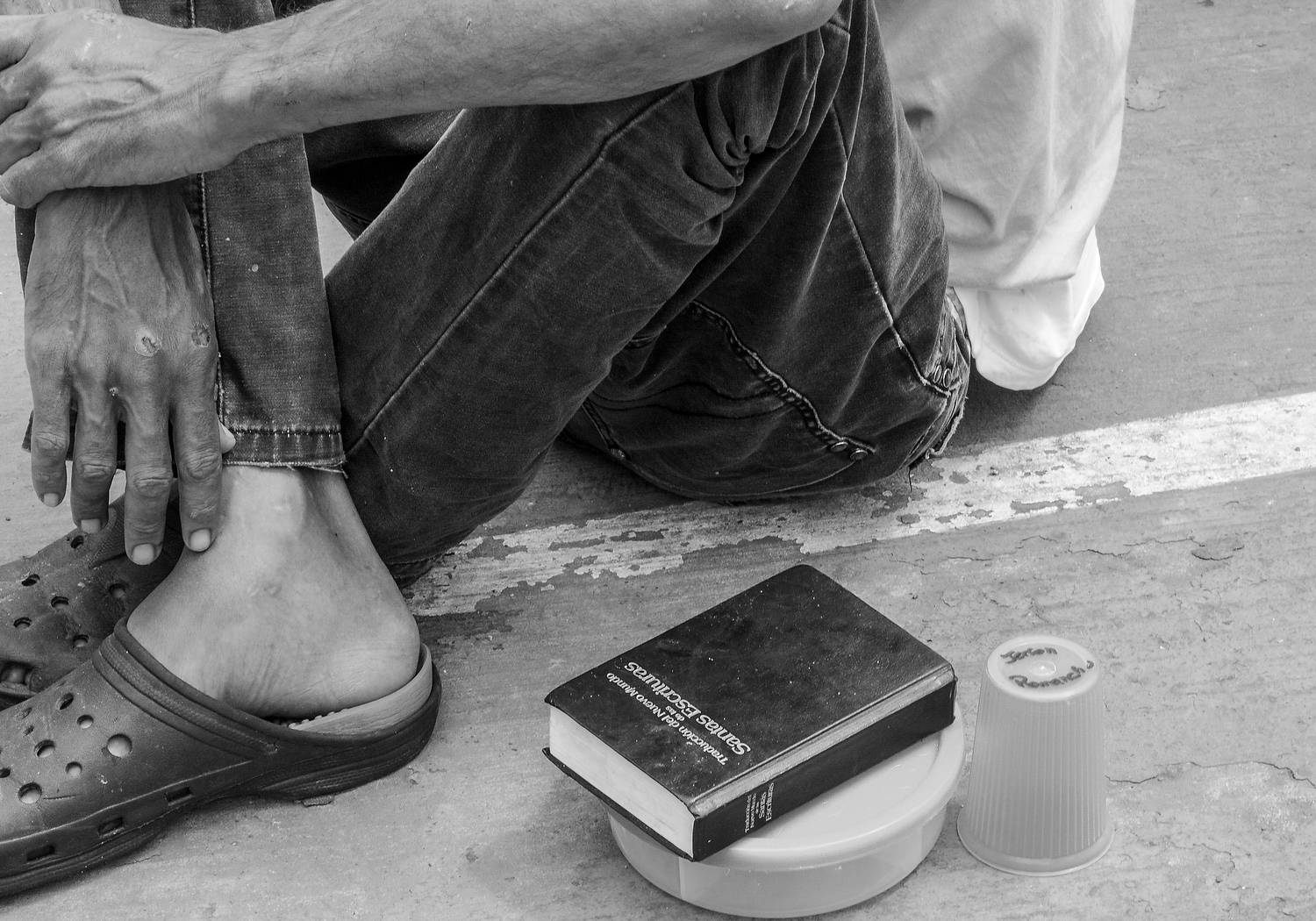

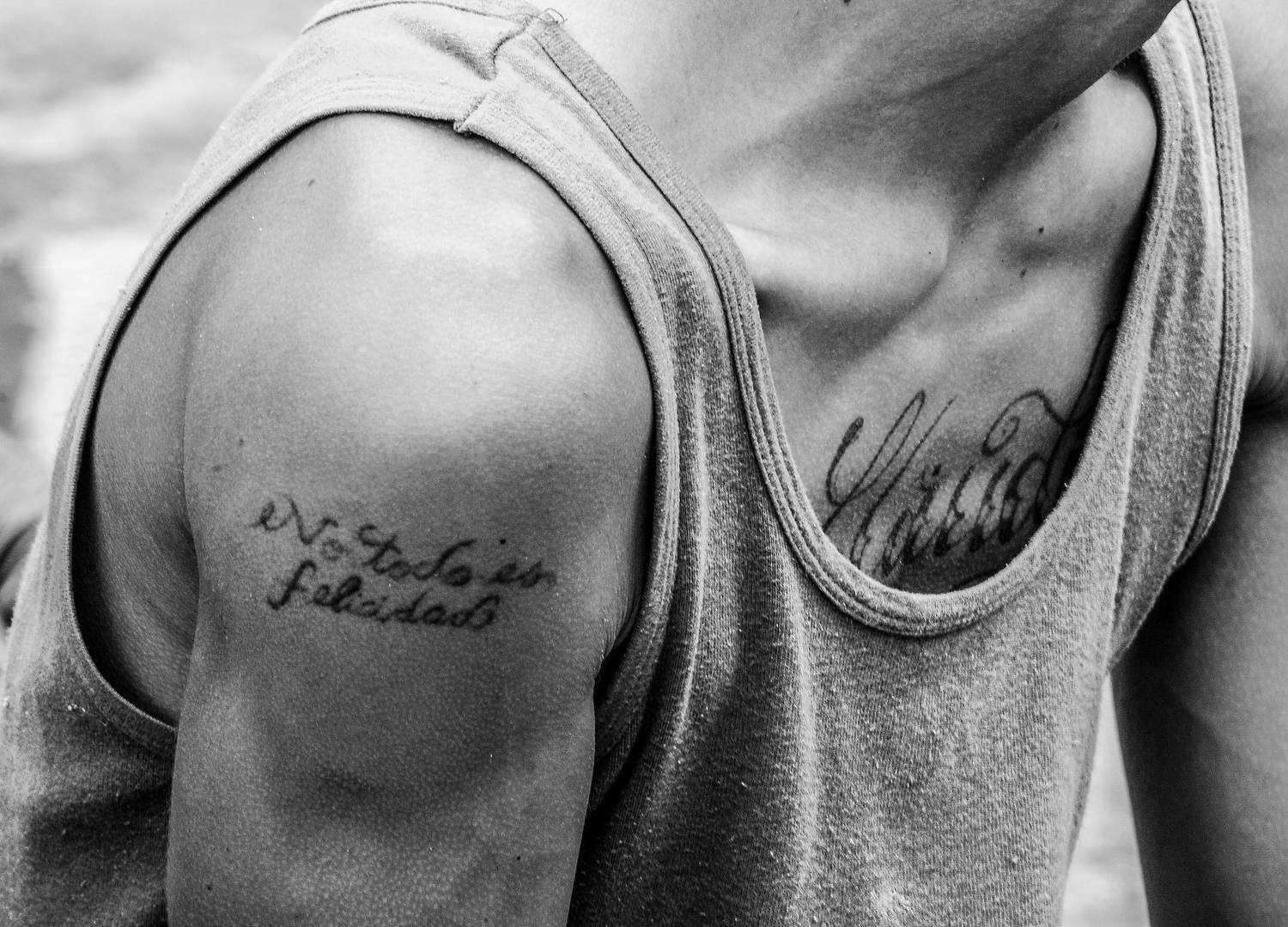

They all had the “kit” which the Ministry of Prisons gave to the inmates: a cup and a cover-less plastic container for food. Many of them did not have shoes, their clothing fit them all quite loosely. Some of them wore surgical masks, which indicated that they were infected with tuberculosis.

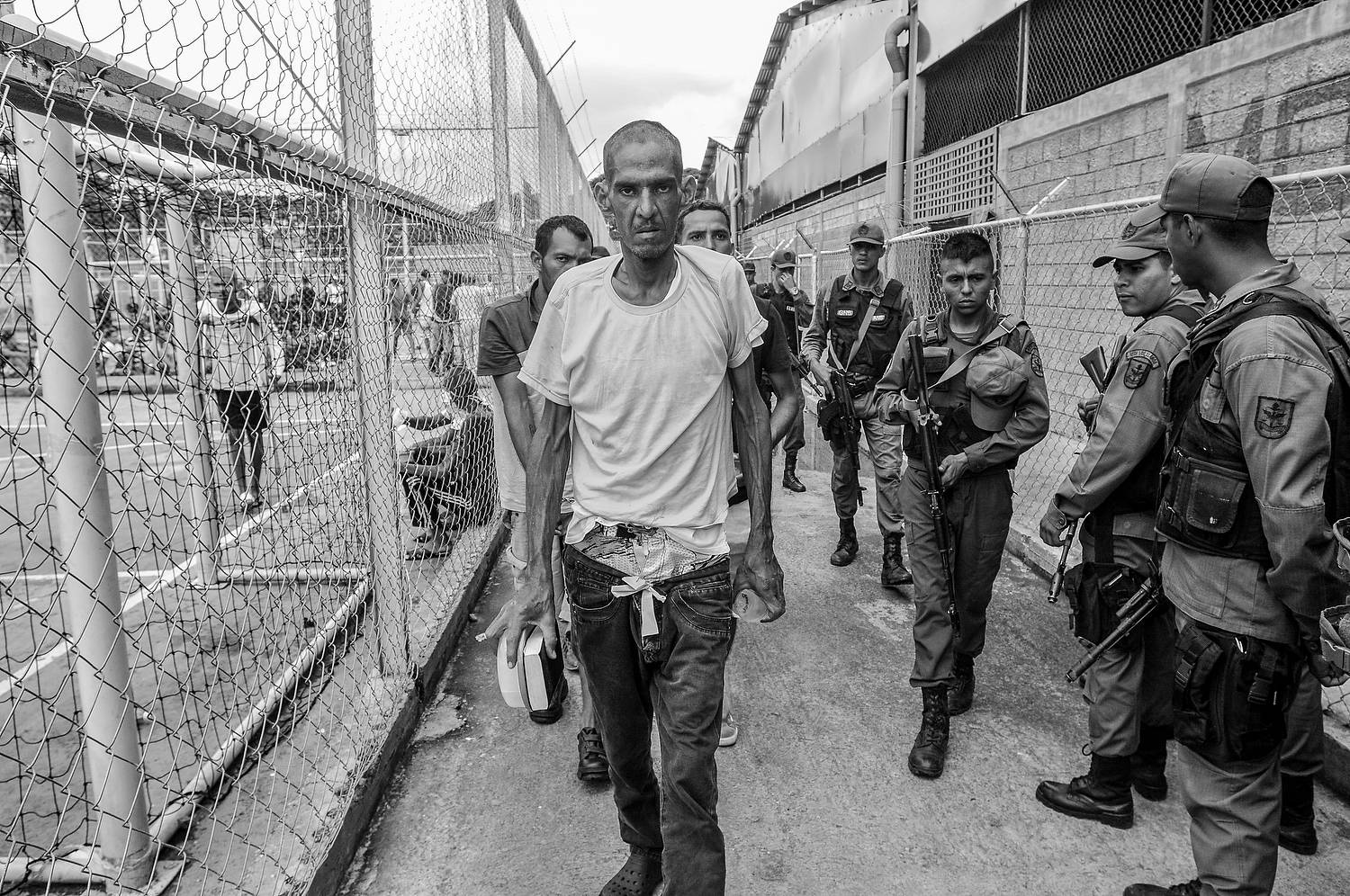

The National Guard arrived and formed a tunnel on one of the courts, where the inspections would take place, before getting on the buses. Within the tunnel, the inmates being inspected started to undress completely.

The first inmate who was being inspected, who was not handcuffed at another prisoner, started to take off his clothes. It was at that moment that I really understood what these people had experienced. The image I saw reminded me of photographs from German concentration camps, during the Second World War, of the extermination camps in Bosnia, but it was incredible that this happened here, in Venezuela, inside a prison, and that those responsible were other prisoners.

I stayed there taking pictures of that man, who only had two t-shirts, his pants, a Bermuda shorts, an underpants and some plastic Croc shoes. Apart from his cup and container, he was clinging to a Bible. His countenance was sad, worn, but his gaze was deep. I saw his name on the container: Jerson Ronaldo. So, I decided to stay and take pictures of him, and so I did until he got onto the bus. Then I continued taking pictures of everything that I could, other inmates who were boarding the bus and the National Guard checking them on the inside. When that bus was full, I received an order to leave the courtyard.

Two and a half hours later, the buses were ready to go. That is when I left and took a picture of the family members, who were waiting at the prison doors. Most of them were women: mothers, wives, sisters of some of the prisoners.

They needed news: their loved ones had been in PGV and they still didn’t know if they had survived the terrible Franklin Masacre.