Pāri mūriem means “over the walls” in Latvian. This collection offers a glimpse of the daily life of 10 young men imprisoned in the country’s only juvenile detention centre. From behind the walls, they give us a feel for what it means to wait out the end of a sentence. Together, we go from their claustrophobic boredom to their desire for freedom.

It is January and it is snowing. In the double-door entry of the Latvian juvenile prison in Cēsis (“CAIN”, Cēsu Audzināšanas iestādes nepilngadīgajiem), I wait for my identity to be verified. Somewhat anxious about the experience to come, I watch the snowflakes fall on either side of the wall, depending on the direction of the wind. I cannot help but make simple yet uncertain parallels on the bit of randomness that leads someone from one side of these walls to the other.

I also wonder what drove me to the point of freely and willingly choosing to go to the other side.

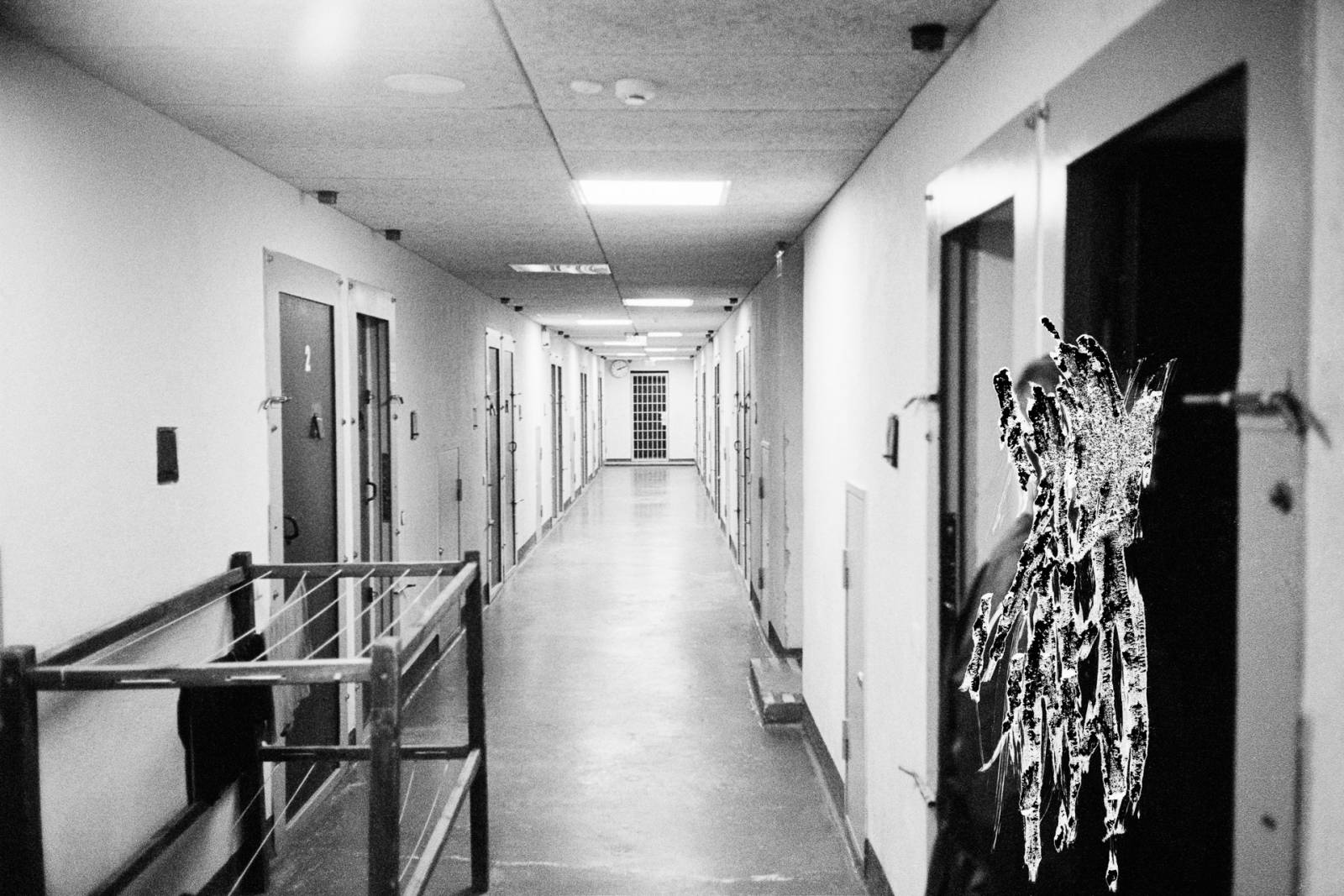

My papers are in order. I am searched. I enter the territory of the prison administration, passing through a succession of doors, bars and barbed wire, and surveillance cameras, static and echoes of walkie-talkies. On the inside, this obsession with security is focused on a mere 39 youths, which surprises me, as the prison housed nearly 250 in the early 1990s. This comparison is striking.

Admittedly, the detention conditions have improved: in 2011 and 2012, the CAIN was renovated using funding from the European Union and Norway. Since then, the young inmates serve their sentences in two-person cells rather than the 25-bed dormitories of the past. They study in a school and work out in a newly renovated sports hall.

With a maximum capacity of 164 inmates, the penitentiary is in no danger of overpopulation. This discrepancy leaves me perplexed. I do not know why these teenagers are incarcerated nor will I try to know the reason. I only know that some of them are serving lengthy sentences. I would like to believe that there are solutions other than custodial sentences.

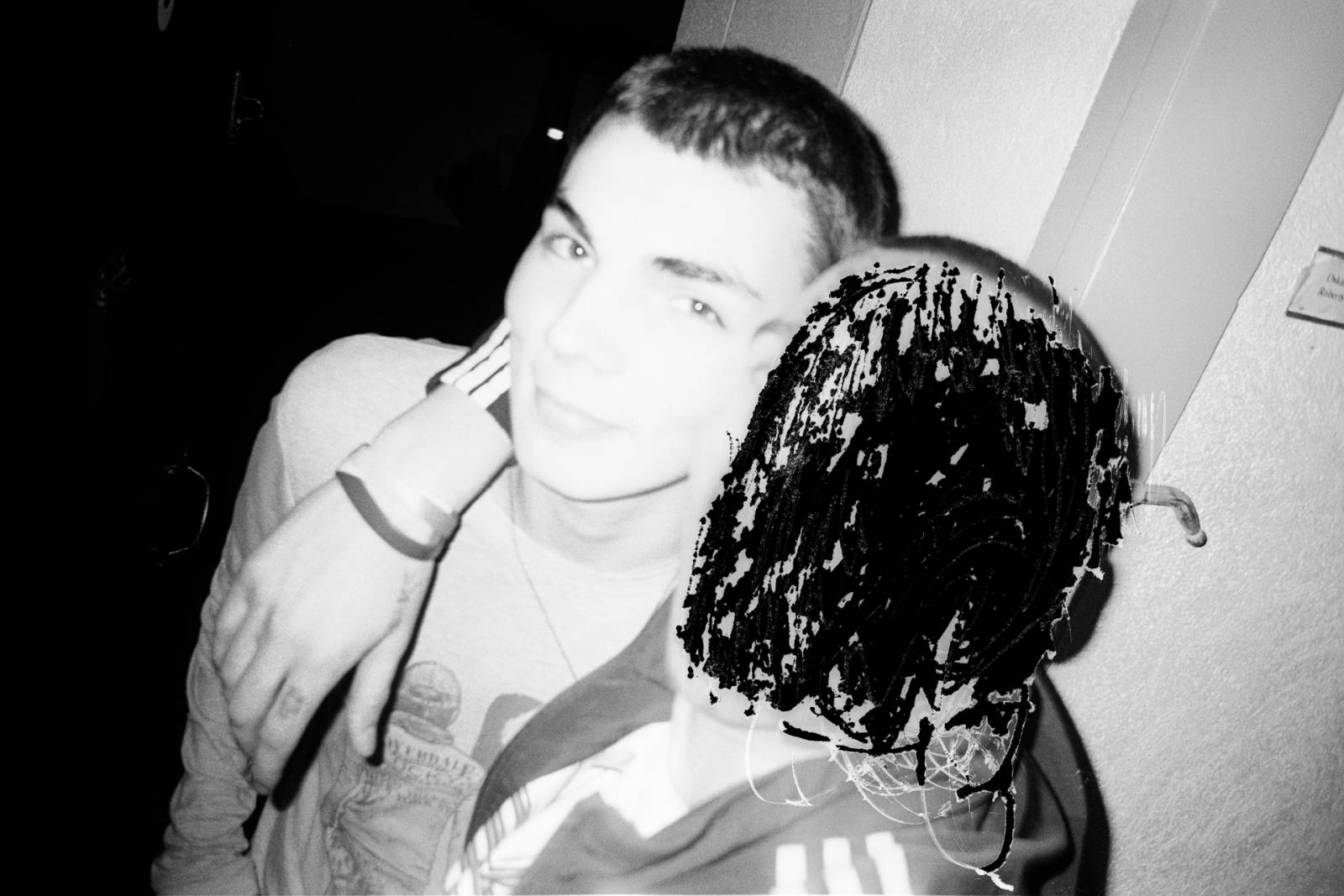

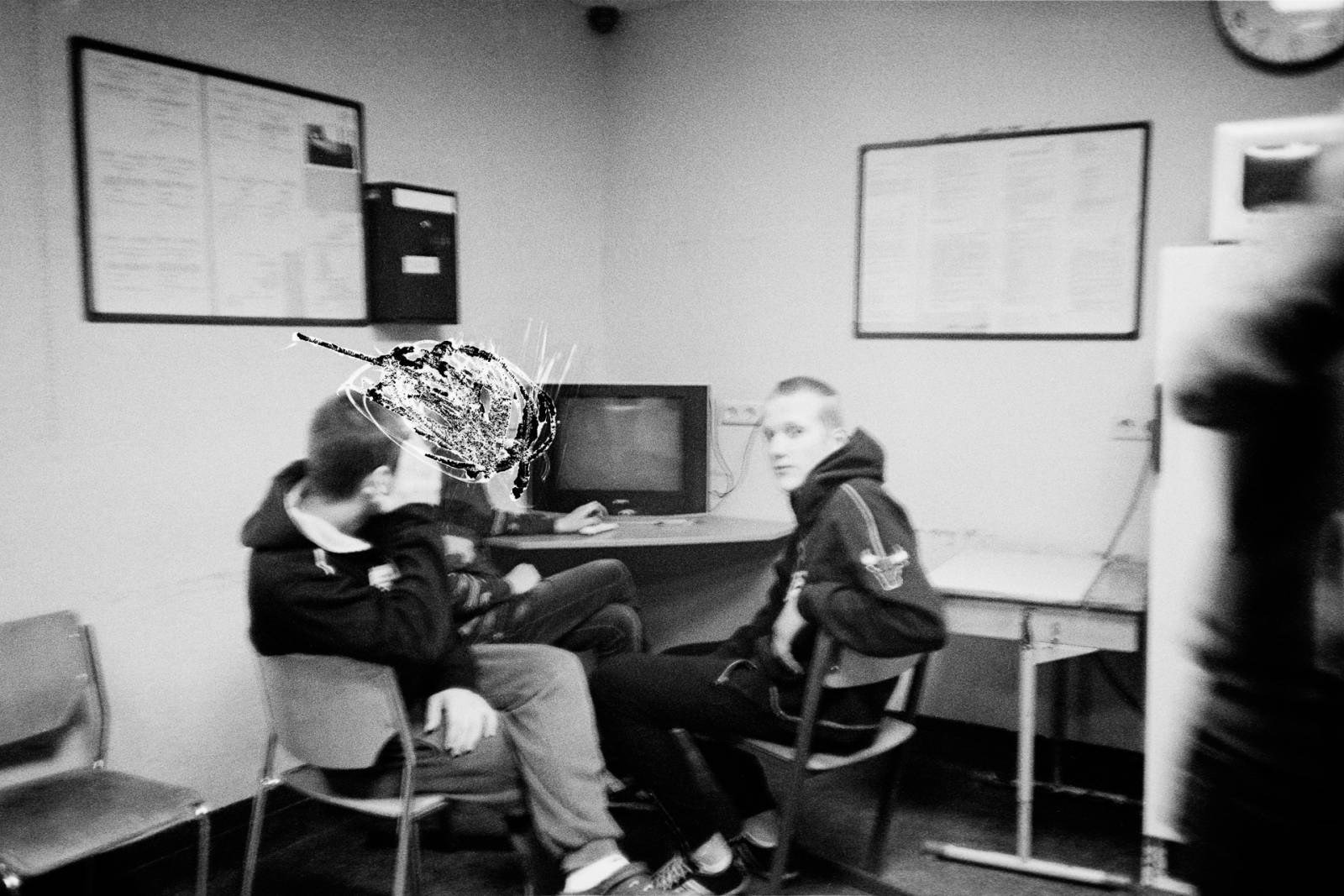

I wait for them in a small room. They enter. We introduce ourselves to each other. I do so in English, using a PowerPoint, and they do so in Latvian or Russian, using a firm handshake. They are between 16 and 21 years old. We understand each other thanks to Zane, the interpreter. A few weeks earlier, these 10 young people accepted my offer of collaborative photography workshops. I came equipped with a film camera and two rolls of film for each participant.

For a month, we met up each weekend to talk about photography.

During the week, they were my eyes on the inside of the prison and I was theirs on the outside, as I agreed to go photograph a place that is dear to each of them. Thanks to them, I travelled around Latvia to photograph views that these young men were no longer able to visit. Each view is accompanied by the portrait of a prisoner, shot in a place they chose in the prison.

Together, we sneak out.

We are called to order and the prison administration insinuates itself in our work. I was not expecting to face any censorship, as everything had been described and approved beforehand, but I am asked to develop the film behind bars so it might be examined by the staff. I am then ordered to remove any “sensitive material” on the negatives using a kitchen knife. Like so, all images which depict inmates who had not participated in the workshops, the prison staff and the perimeter wall are altered. It is not important that these elements were already blurry or the individuals had their backs turned – I must scratch.

— Jérémie Jung.