Nicolas Sallée. First, it is important to understand the nature of these places of confinement. The graphic novel illustrates daily life inside a so-called “secure unit” at the Cité-des-Prairies institution in Montreal. These units accommodate boys remanded in custody or sentenced to the most severe punishments under Canadian juvenile criminal law: “custody and supervision sentences”. In Quebec, these units can be open custody or closed custody; the graphic novel depicts a closed custody unit. In open custody units, bedroom doors remain open. However, in both cases, any young person who leaves without authorisation is liable to criminal prosecution for escape: both are, therefore, legal incarceration facilities. To complicate matters further, Cité-des-Prairies also has several “protection” units, reserved for young people who have not been convicted of a crime but who have been taken into the care of youth protection services. In some less populated areas of Quebec, there are so few young people convicted of crimes that they are placed with those in secure protection units.

This mix may seem strange, but it reflects the paternalistic mentality that has historically defined the imprisonment of young people considered deviant: if we deprive them of freedom, it is ultimately for their own good, protection, education, or rather, as we say today, rehabilitation and reintegration. This paternalism was explicit in Canada’s first Juvenile Delinquents Act, adopted in 1908: to meet the supposed needs of young people, judges were able to deliver indefinite custodial sentences, without opposition. Fortunately, there were major reforms to Canadian juvenile criminal law in 1984 and 2002, which helped recognise the rights of young people, such as the right to counsel. Since the mid-1980s, young people in secure units have been granted an increasing number of non-negotiable rights, such as visiting, telephone and hygiene rights. These rights are intended to bring living conditions closer to those in the outside world. The link between custodial units and external monitoring institutions was also strengthened in these years. As of 2002, any young person with a custody and supervision sentence has served the last third of it in the community, under the supervision of probation officers, known in Quebec as youth delegates (délégués à la jeunesse).

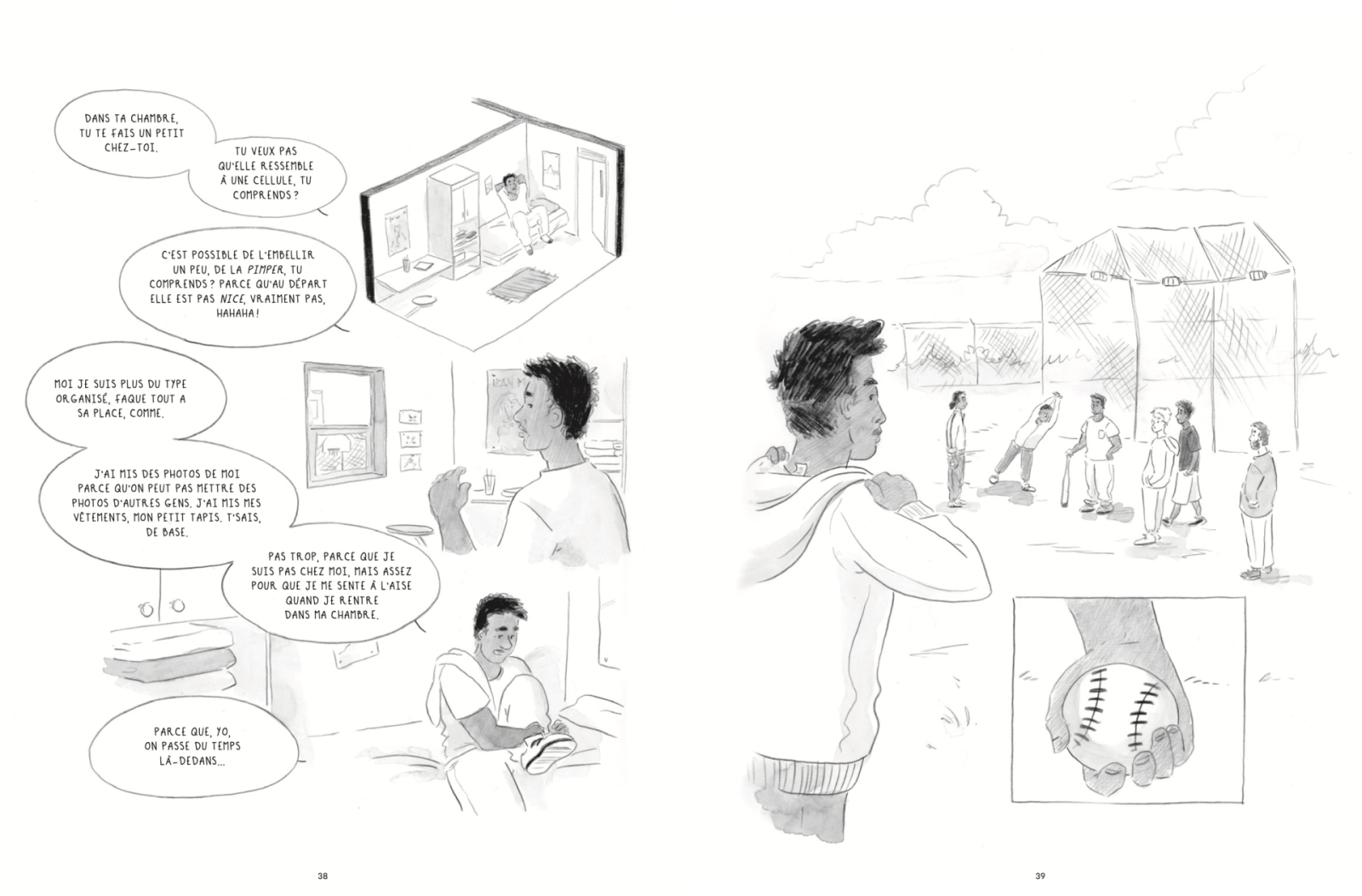

However, this paternalism is far from obsolete. Today, young people are caught in a double bind. The prison is fenced in, the doors are closed, and there are a multitude of rules dictating when they wake, sleep, do activities, how they move, speak, and interact. The constraint of confinement, which takes its toll on the body, is intrinsically coupled with the constraint of rehabilitation, as Foucault describes in Discipline and Punish. The latter constraint demands that young people not only “do their time”, but also use this time to reshape their behaviour, tame their emotions, and rectify their thoughts. Young people often resist these expectations, refusing to do more than serve their time, as a means of protesting against the demands of their educators. This modernised, cognitive-behavioural approach to self-transformation is not clear cut. On one hand, it allows young people to take part in numerous educational, clinical, cultural and sports activities, which they would undoubtedly have less access to in a real prison. On the other hand, it permits round-the-clock deployment of behaviour-correcting discipline, often in the form of isolation, i.e., “withdrawal”: young people are locked in their bedrooms or in an empty room to reflect on their poor behaviour.

See below for pp. 38-39 of the graphic novel¶