In terms of accessing habitation solutions, the specific challenges met by people leaving prison fall within a context that goes far beyond the carceral issue. It is increasingly difficult to find housing, even for people with employment and a stable situation. Everywhere, housing prices are skyrocketing, and salaries cannot keep up. In Ontario (Canada), rent prices have climbed 2.3% per year over the past ten years, compared to 0.4% for salaries between 2000 and 2013. In Dublin (Ireland), rent increased by 90% between 2012 and 2022. In France, between 2000 and 2022, housing prices rose by 160% – three to four times faster than average income. Housing is becoming unaffordable, and the housing crisis has become the norm.

Numerous people emphasise that the problem has more to do with the affordability of housing than the lack of availability. Reza Ahmadi of the John Howard Society of Ontario notes that “the housing options being built now are big apartments or family homes. What we need are small, more affordable housing options. As it is, everyone in need has to fight one another for these spaces.”

This context makes accessing social housing extremely complicated.

The same holds true regarding emergency accommodation schemes: the number of people on the street is rising exponentially. In France, the Fondation Abbé Pierre estimates that of the 1,098,000 people without personal housing, nearly 330,000 are homeless. Some live in group accommodations, in hotels, in makeshift shelters, or on the streets. The Fondation is concerned by the record congestion of the emergency call number 115: in November 2023, nearly 8,000 people, including 2,400 minors, were turned away every night due to a lack of emergency accommodation spaces. In autumn 2023 in France, several mayors of major cities announced a plan to sue the government over the thin provisioning of its action in favour of homeless people. They alerted the French government of the practical difficulties of overcoming insufficient state resources dedicated to the emergency accommodation system.

Additionally, the Social Union for Habitation (Union sociale pour l’habitat) notes that nearly 2.4 million households are currently waiting for social housing, i.e. 162,000 more than in 2021. For the Union, this figure is cause for concern, because social housing providers only grant an average of 400,000 allocations per year – even less in 2023. The average timeframe for obtaining housing is lengthening, by 20 to 30%, depending on the area. In Stockholm and Toronto, the wait time for social housing is ten years, and in Amsterdam that wait can stretch to 13 years.

Access to habitation for disadvantaged people leaving prison is especially concerning in this context, as Reza Ahmadi explains when describing the situation in Canada: ”When the housing supply is so limited, it is much harder for people on the margins of society, such as those leaving prison, to obtain housing. Demand is nearly 500% higher than supply. Imagine a person in conflict with the law in this situation.”

Several of the people interviewed by Prison Insider hinted that the current housing crisis creates fierce competition between various groups of people in need. This complicates housing acquisition for associations who want to offer habitation solutions.

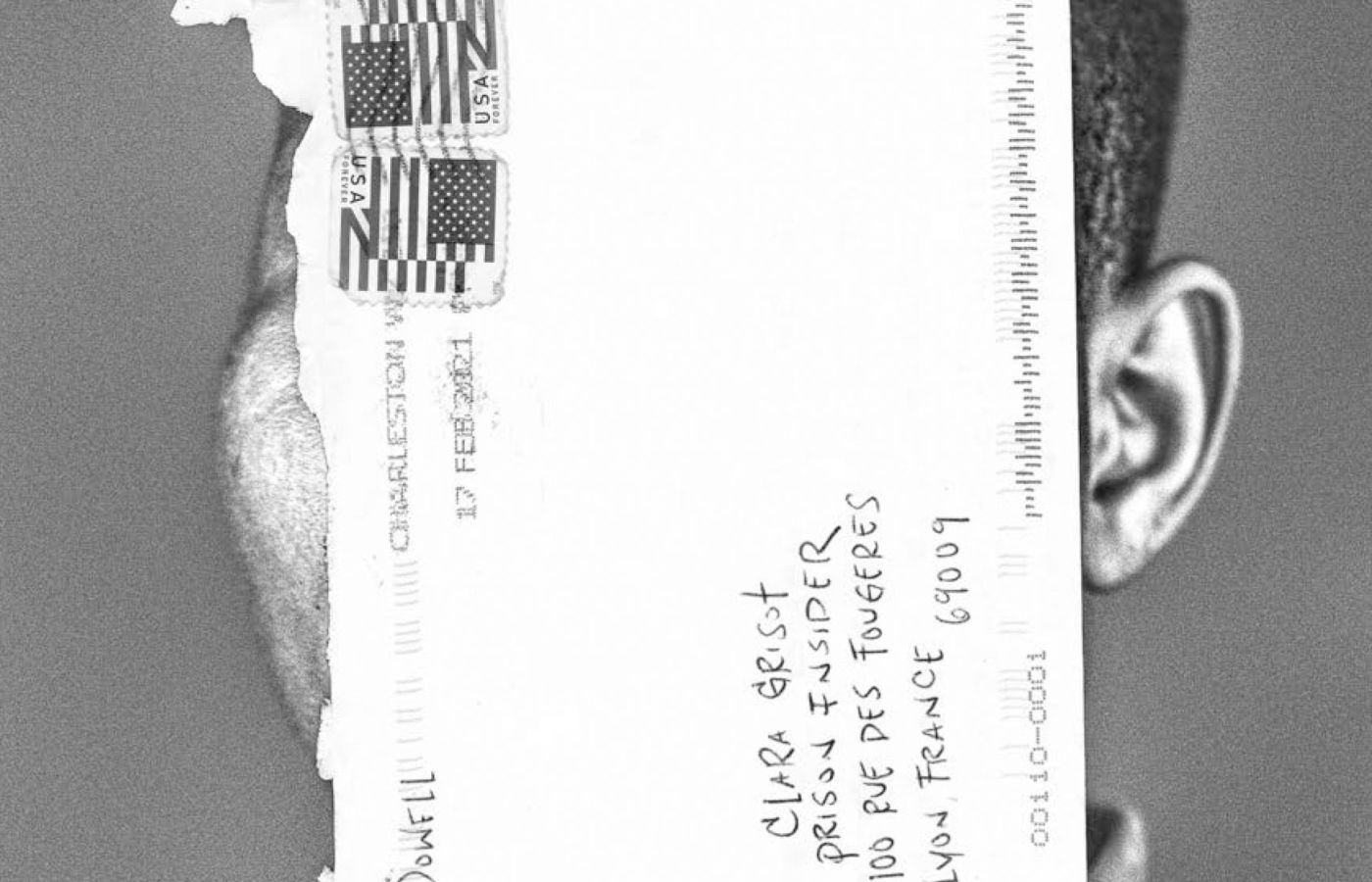

Marine Tocco is Head of the Justice and Social Cohesion division at Les Foyers Matter, an association based in Lyon (France) that accommodates, in particular, people leaving prison as part of sentence adjustments. She describes the difficulties faced by the association in expanding its offerings: “We try to increase rental housing stock in a thousand different ways: property provisions, a collaboration with a cooperative that organises life annuity sales, etc.” A large part of her work involves increasing stock. If not for these difficulties in accessing housing, Les Foyers Matter would be able to accommodate many more people as part of their sentence reductions.

Property is not the only consideration that must be taken into account when offering habitation solutions to people who have just been released from prison. Some options are not worthwhile, Marine Tocco explains: “We are careful to avoid certain neighbourhoods and places on the ground floor with bars. We ensure that the housing is as accessible as possible.” Options are all the more limited because most recent constructions are located far from city centres. “They are not viable solutions for the people we work with because the vast majority of social services and mental health services that many formerly incarcerated people need are located in city centres”, explains Reza Ahmadi.

Pierre Mercier, Director of the association Le MAS (Lyon, France), stresses the current impossibility of finding somewhere to live, whether in social housing or elsewhere. He highlights the necessity of urgently acknowledging this serious crisis. “People with salaried positions, who are not leaving prison, who are not foreign nationals, can no longer find housing. So of course, obtaining housing for people who are leaving prison is a particularly complicated matter, because they are among the most vulnerable and disadvantaged. They represent various concerns that society does not want to consider: they are primarily men, young men specifically, with potentially high-risk behaviour or mental disorders. Our current society is merit-based, so it can seem difficult in times of scarcity to grant housing to people who have behaved badly. Consequently, prison sentences do not end once they have been served: they continue afterwards. The sorting of ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ occurs whether priority lists have been drawn up or not.”