“Walking into a classroom was like walking out of prison”

Inside the prison education programmes changing communities

Source: In.Visibles

See the panoramaPrison population is on the rise across the world. While some governments claim incarceration is the most effective tool to tackle crime, analysist say imprisonment alone only feeds the cycle of violence and that education helps transform societies for the better. Here, some of the most groundbreaking projects, and the people behind them.

This article was first published on In.Visibles website. It was written by Josefina Salomón and the photos were taken by Patricio A. Cabezas.

At the end of the main corridor, a sign with the names of the 50 people who have graduated since the university was inaugurated in 1985.

Diego Cepeda, 38, had never thought of pursuing a university degree, let alone becoming a lawyer. One afternoon, as he finished high school in the only federal prison in the city of Buenos Aires, Argentina, he looked out of the window to a courtyard where a group of other people deprived of their liberty played football. They trained for two hours every day.

“I want to be there,” he said to himself. “There” was the Centro Universitario Devoto - the CUD, as everyone calls it - the first higher education programme in a prison in Argentina, and one of the first in Latin America.

While serving their sentences, people in prison can study undergraduate courses such as economics, psychology, philosophy and literature, sociology and law, as well as take part in workshops, lectures and seminars. Professors from the University of Buenos Aires, Argentina’s largest public education institution, teach the classes, but it is the students who are in charge of the programme and the space: they look for potential students, clean the rooms, cook meals and organise activities with guests “from the outside”.

Cepeda, who had already served time in other prisons, was transferred to Devoto in 2008. He was 23 years old. He saw that the CUD offered him the possibility to develop new tools for life outside of prison. He started taking computer workshops, helping in the kitchen, cleaning. Finally, he enrolled in Natural Sciences. The idea was to spend as much time as possible outside the cellblock where he lived, one of the most violent in the prison. His main objective was to survive.

“I wanted to spend as much time as I could in the CUD. There are events there, people come in from the outside who you can talk to, who bring new ideas. It breaks the logic of confinement. It’s still a prison, but it’s different. It takes you away from the day-to-day reality. Spending time there was a way to keep me grounded,” says Cepeda.

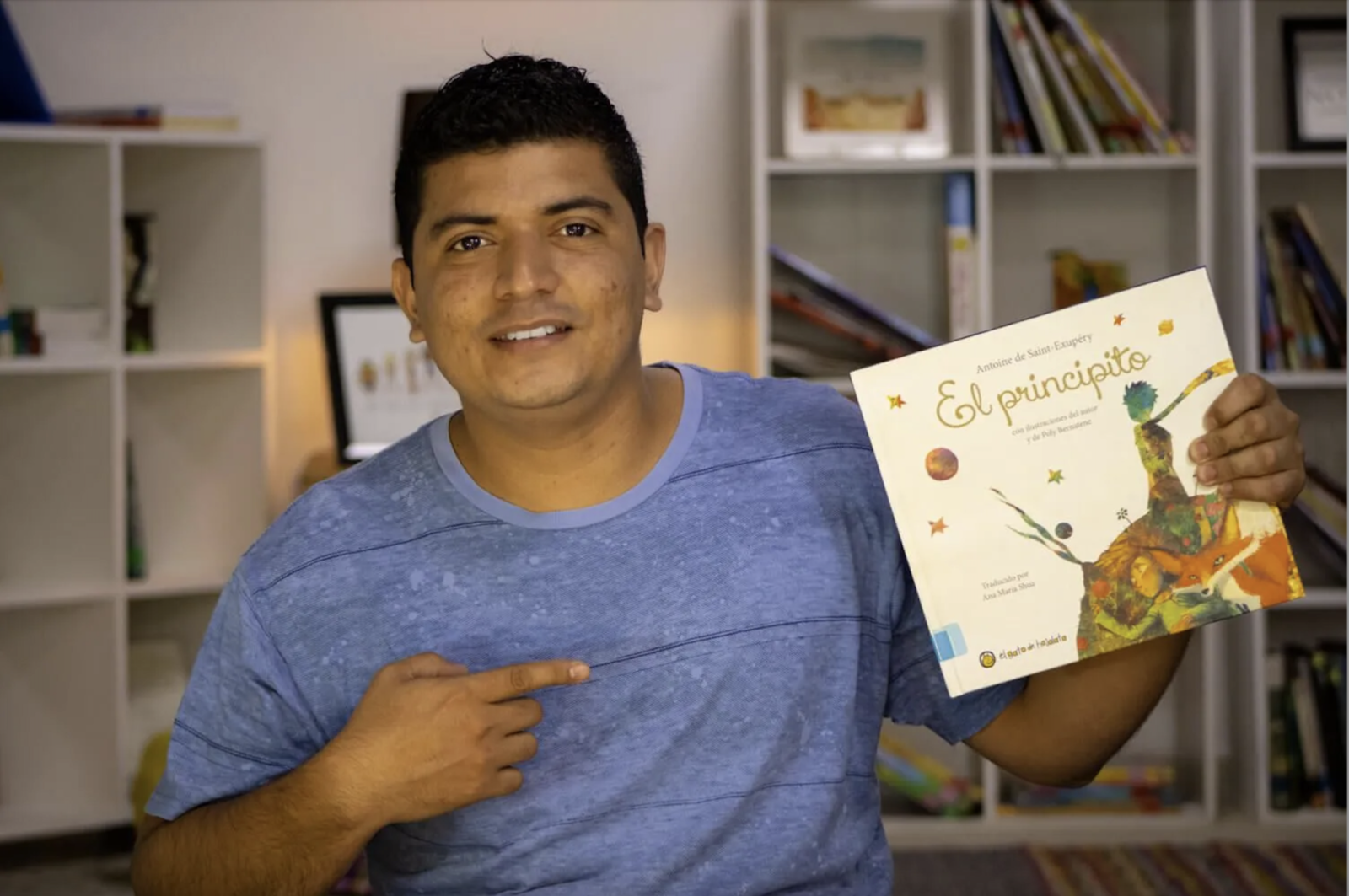

To get to the CUD, you must go through three huge, barred gates, two metal detectors and decades of history. Behind the last gate, made of black iron bars, everything changes. The guards and the prison stays behind. The walls of the narrow corridor are crammed with posters announcing events, course calendars, general advice. A handwritten letter from Pope Francis sent in 2023 hangs in a golden coloured frame. Each of the faculties that make up the CUD has its own classrooms with tables, chairs and blackboards. There is a main room where meetings and events are held.

At the end of the main corridor, a sign with the names of the 50 people who have graduated since the university was inaugurated in 1985, when a group of students negotiated with professors recently returned from exile at the end of Argentina’s most brutal dictatorship to open the first free university inside a prison in Latin America. People in prison refurbished, with their own labour and money, what used to be an abandoned wing of the prison. It was a collective effort, “very impressive” as people recall many years later.

The place is an abyss away from the rest of the prison complex, where 1,541 people survive the lack of space and poor living conditions, among many other problems, according to the most recent report by the National Penitentiary Procurator’s Office. The complex, which was a clandestine detention and torture centre during Argentina’s most recent military dictatorship between 1976 and 1983, is located in one of Buenos Aires’ wealthiest residential areas.

"Walking into a Bard classroom was like walking out of prison, it freed my mind and my soul."

Building citizenship¶

In-prison education programmes are gaining popularity as countries look for alternative ways to deliver sustainable justice against the backdrop of a growing global prison population. In Argentina, for example, the number of people in prisons quadrupled between 1996 and 2022. Most are in pre-trial detention, without conviction - as in most parts of the world. The vast majority come from marginalised backgrounds, with difficulties in accessing education. The impact of imprisonment is particularly harsh for women, who are often heads of households, and for transgender people, who face intersecting forms of discrimination. Even with differences, this is the case throughout Latin America, and the world.

Those behind education projects in prisons say that learning is an essential part of any strategy that looks to advance social justice and reduce violence. One of them is Baz Dreisinger, journalist, author and founder of Incarcerations Nations Network (INN), an organisation with chapters in a dozen countries around the world that researches, disseminates and promotes innovative prison reform and justice initiatives. Dreisinger has seen it all. From literature and drama programmes in women’s prisons in Thailand, to restorative justice projects between victims of the Rwandan genocide and their perpetrators, to education in semi-open prisons in Australia.

“There are many programmes around the world that impress me. Justice Defenders in Kenya and Uganda, which offer careers in law, for example, are revolutionary because they empower people in prison and their communities who also end up benefiting from these new skills. In the United States, there are also very good examples of programmes that were redesigned with the idea of reintegration, of helping prisoners complete their studies when they return to their communities and thus benefit them as well,” Dreisinger explains.

The United States, one of the countries with the highest incarceration rates in the world, is home to a host of education programmes for people deprived of their liberty. Dyjuan Tatro, Senior Government Affairs Officer at the Bard Prison Initiative, says that education in prison in the United States, one of the countries with the highest incarceration rates in the world, helps incarcerated people overcome the racism and poverty that relegated them to the worst schools and put them on a path toward the worst life outcomes, including in some cases, incarceration. “(Education) fundamentally changes the trajectory of their lives. Not only do people who earn degrees in prison have some of the lowest recidivism rates, they also, and more importantly, have the most successful post-release outcomes.”

Like Cepeda in Argentina, Tatro, says being able to study while in prison gave him something great to work towards. “Prisons destroy pride. Prisons isolate and further marginalise people. Walking into a Bard classroom was like walking out of prison, it freed my mind and my soul. Being a student, and not a prisoner, gave me pride. Siting in those classrooms connected me to my peers and the world. College is the antithesis of prison.”

The most successful programmes are those that tend to go beyond the purely academic aspects. This is what Ramiro Gual, a researcher and professor of law in Argentina, who has been teaching at Devoto since 2016, calls “building citizenship”. “In Argentina, the management (of education programmes) is left in the hands of the students, and that is where they generate a lot of skills and knowledge that enables them, in the future, to set up their own projects, their own cooperatives,” explains Gual.

In Argentina, the CUD and the CUSAM, a university that operates in Unit 48 in San Martin, in the greater Buenos Aires area, have student centres that operate independently, with rules and elections of representatives who intercede with the authorities when students have specific requests. In this way, the programmes not only create professionals but also citizens capable of defending their rights and those of their communities.

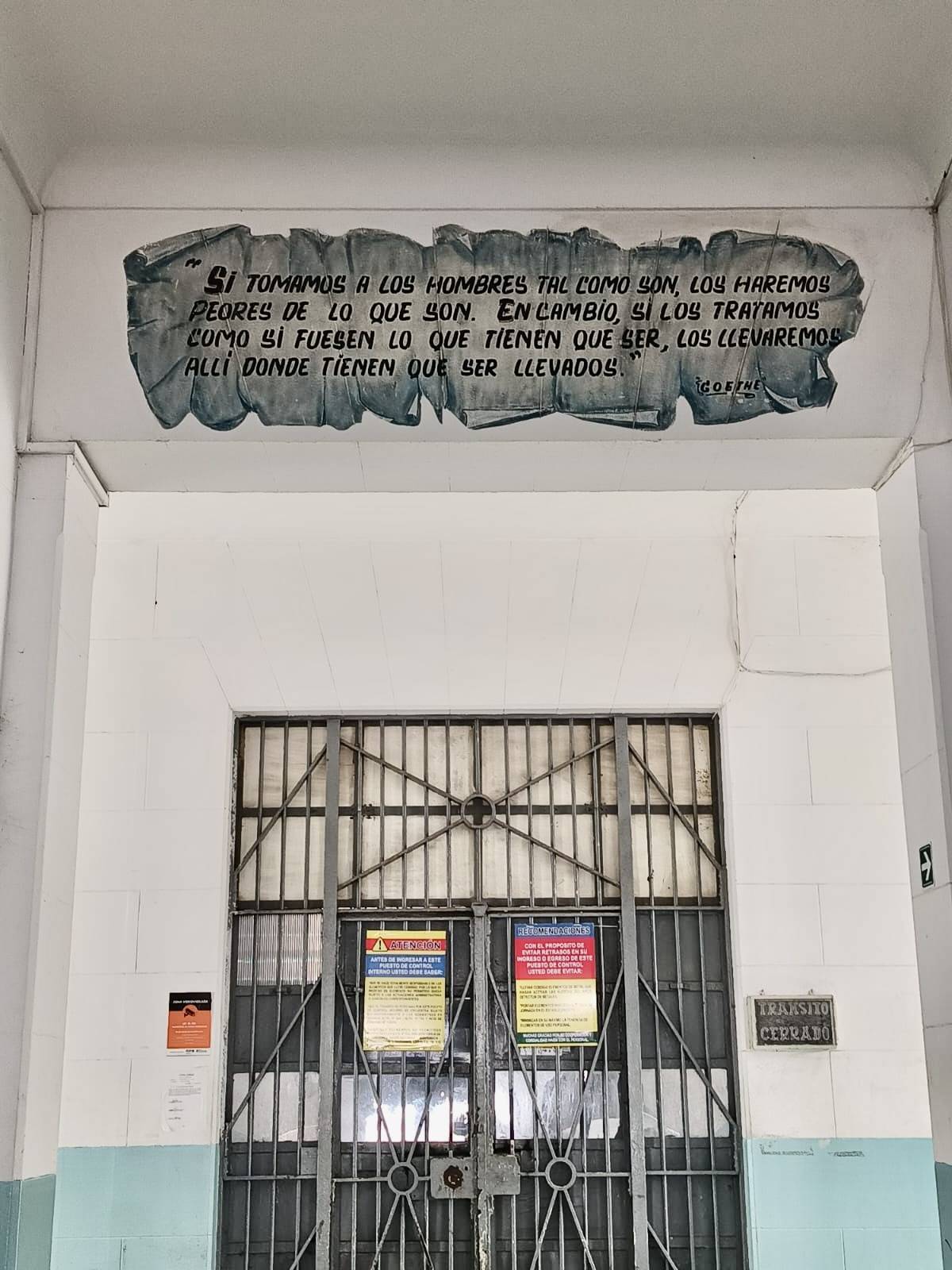

“Education is a form of liberation, of transformation”, says Anayanci Fregoso Centeno of the University of Guadalajara in Mexico, who teaches in several detention centres. She says the main challenge is to ensure that the education offered inside prisons is aimed at emancipation. “We have to offer something that helps them to make decisions, to demand rights, to think about education to build critical thinking. In Mexico, this is a path to peace.”

By studying law, Diego was able to better manage his own legal process and help other people in prison.

Life after prison¶

Regaining freedom is a complex process for most people who experience imprisonment. States often provide little support for those who need to reconnect with their families and communities, or to find work, which is particularly challenging for people with criminal records. In Argentina, there’s a government agency that, in theory, should accompany the process, help people who spent time deprived of their liberty find work and regain social ties. In reality, the lack of funds and, in some cases, of political will in a context of economic crisis, does not help.

When, in 2016, Diego Cepeda started considering his options and what would come after confinement, he saw that lawyers who studied at the CUD had the best chance of working because they could do so independently, despite having a criminal record.

Becoming a law student also helped him in his cellblock.“I was useful for the other guys because I could get information for them. At the CUD I could consult the Penal Code, ask questions about their cases, I served as an advisor”, he explains.

By studying law, he was able to better manage his own legal process and help other people in prison with individual and collective claims. Today, his clients include people currently housed in Devoto. They choose him because he understands, from experience, what they need.

Cepeda graduated in 2021, when the isolation measures of the pandemic were still in force in Argentina’s prisons. After a few months, he was released.

Silvana Ortiz, who was released from Unit 46 in San Martín a year and a half ago, says that, for women, most of whom are heads of households, the challenges that come after being released from prison can be even greater. “When I regained my freedom, I looked for work everywhere, but there was nothing. They [the government agency] told me that they were going to help me, but nothing came up. There are many cases of women who, after their release, say that they were better off in prison than outside”, she says.

Things changed when someone recommended that she approach Esquina Libertad, a printing and audiovisual production cooperative made up of current and former people deprived of their liberty and their relatives. Coope, as they all call it, was formed in 2010 in response to a need that had been identified by several relatives of people deprived of their liberty during conversations they had while queuing outside the Devoto prison. Today it employs around 500 people and works closely with educational projects in half a dozen prisons, including Devoto and San Martin, where CUSAM operates.

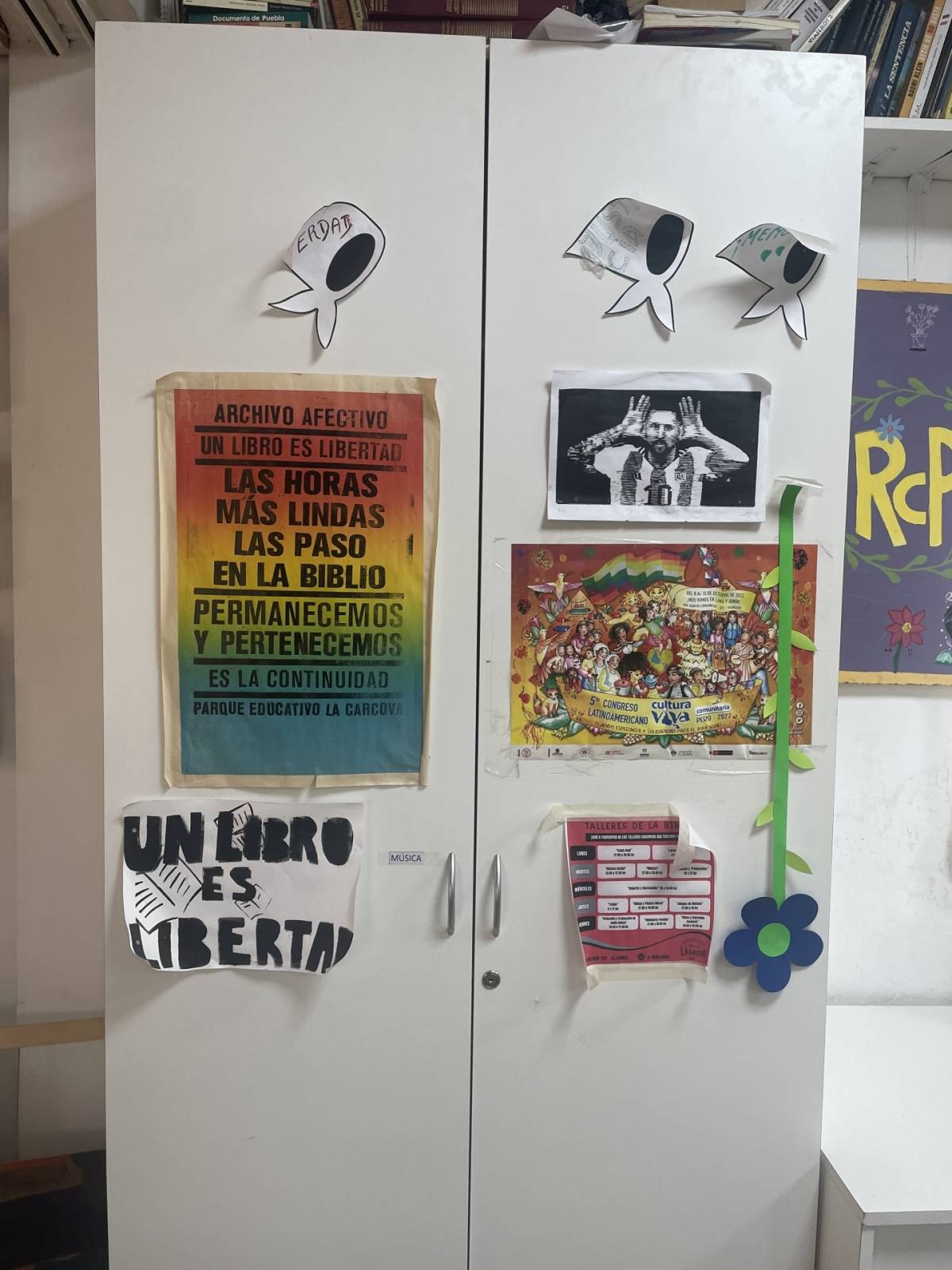

CUSAM, the university inside the prison in San Martin, is another educational project with a strong focus on what happens after people are released.

In its classrooms, men, women and even guards study together and can choose between social work, sociology or a dozen workshops. The emphasis is not only on academic achievement, CUSAM encourages students to use what they learn to develop projects to benefit their communities.

One of them is a public library in La Carcova, a marginalised neighbourhood close to the prison, which was developed by sociologist Waldemar Cubria after his release from prison.

In Argentina, lack of resources is a big barrier as programmes often lack independent budgets.

Challenges¶

Some 185 people deprived of their liberty are currently studying at the CUD in Buenos Aires. More than 800 are pursuing other courses at Devoto. The CUD does not have a limit on the number of students it takes. The only requirement is to have completed secondary school. Paradoxically, the demand does not overwhelm the capacity of the space. The commitment and dynamics of the place are not for everyone.

Securing students is not the only challenge faced by education programmes in the context of incarceration. In Argentina, for example, lack of resources is a big barrier as programmes often lack independent budgets. Their funding depends on what each faculty devotes to them - which has been decreasing over the last year - and largely on the personal commitment of the teaching staff.

Gual says that when budgets are cut, the main impact is seen in the living conditions in prisons. “If living conditions in prisons worsen, who is going to be in a position to plan to go to high school, finish high school and enter a university programme?”, he asks. Questions about the future are a constant in conversations with teachers, students and released prisoners. Gual says that, despite everything, they choose to continue moving forward, to continue building for the future.

Dreisinger says that the list of challenges facing prison education programmes begins with the dichotomy between two institutions that have opposing purposes: “There are the universities, which promote freedom, and the prisons, which exist for confinement and projects that try to work with a population that, in most cases, has survived great trauma.”

In addition, there is what happens on the outside, after people regain their freedom. “The issue of reintegration is one of the main challenges facing most education programmes. A lot of very good work is being done inside prisons, but in most cases not enough is done to keep in touch with the students when they come out and face the biggest challenges,” says Dreisinger.

The crisis is also affecting those who complete their degrees. Cepeda, who graduated as a criminal lawyer at the CUD, for example, already has clients, but finding a job is not always easy: “The experience in prison, and afterwards, is abysmally different between those who have access to education and those who don’t. A degree doesn’t make you more or better. A degree doesn’t make you more or better than anyone else, but it changes your life”, he says, as he prepares to return to Devoto to visit his clients, who call him because they know he speaks from experience.

Ricardo Alfonso Cepeda Orozco, a PhD candidate in education management at the University of Guadalajara, Mexico, says that the experience of people who have gone through education in contexts of imprisonment is key to encouraging others to study.“I have a friend who was in prison most of his life, got out and went to university. Now he is almost finishing his doctorate and he goes to prisons in California and teaches poetry, literature and art and through that experience he helps change the lives of other young people because they are people from his own community who see him succeeding and several of those kids are already in university or doing other things.”

Cepeda Orozco, who experienced confinement in the United States and was deported to Mexico, says that having people who experienced incarceration lead education programmes is key. “As I see education programmes for incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people getting better, I see more people who have been convicted of the worst of the worst leading the social transformation of their communities.”

“People have a fantasy that when someone gets out of prison after 15 years living in terrible conditions and has a criminal record for another 10 years that after all that they will somehow be able to find a well-paying office job in a nice part of town”; says Matias Bruno, a professor at CUSAM. “But that’s not what happens. At CUSAM we propose a different approach. Education, in the end, is the best security policy because it gives people the tools they need to stay away from crime.”