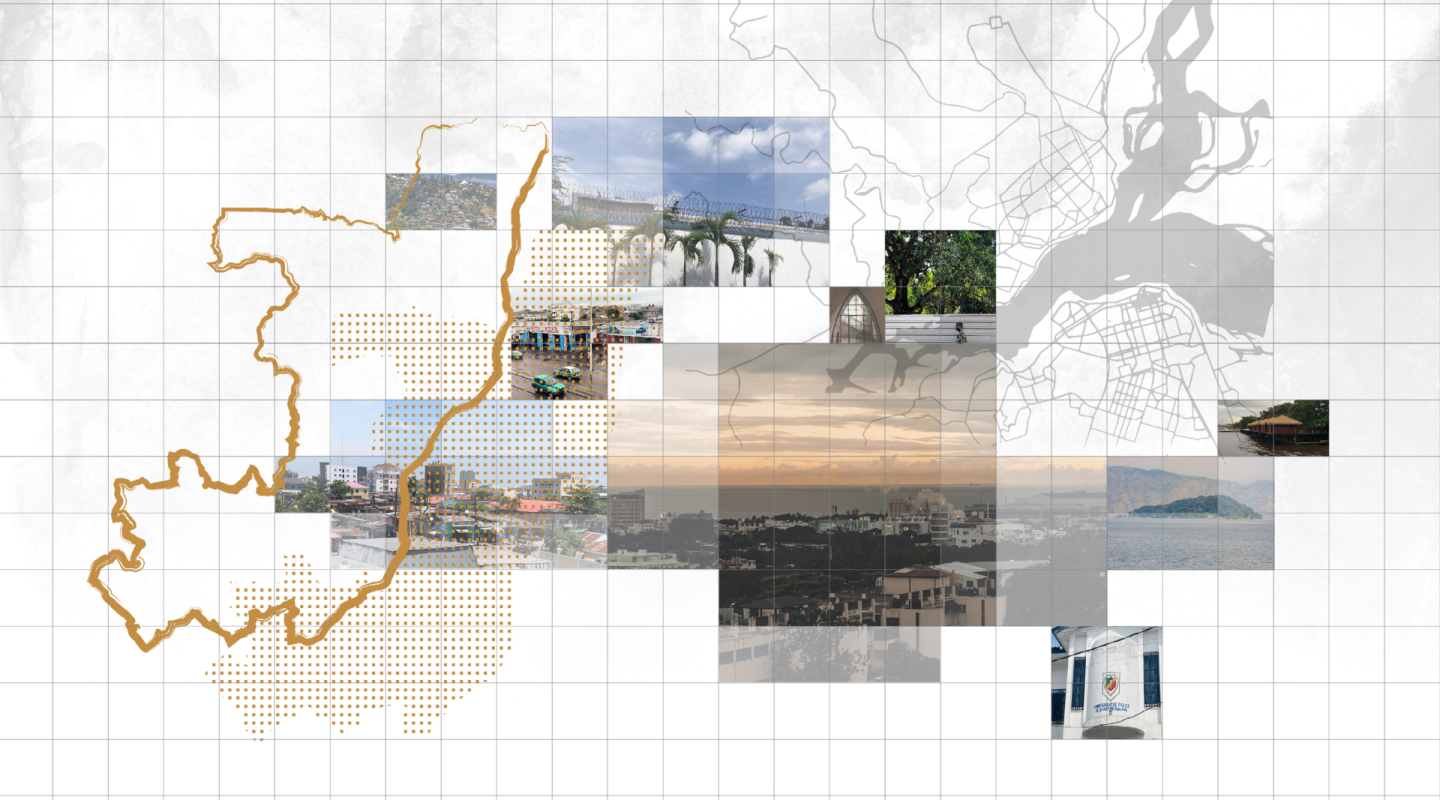

Republic of the Congo

Capital city — Brazzaville

Incarceration rate (per 100,000 inhabit…

i09/2019Country population

i2022Type of government

Human Development Index

0.571(153/191)

i2021/ UNDP, Human development summaryHomicide rate (per 100,000 inhabitants)

Data not disclosed

Name of authority in charge of the pris…

Ministry of Justice, Human Rights and t…since 1991

Total number of prisoners

1,600This figure corre…

i02/09/2022/ prison serviceAverage length of imprisonment (in mont…

Data not disclosed

Prison density

313 %The cited prison…

Total number of prison facilities

An NPM has been established

Female prisoners

2.1 %This figure corre…

i02/09/2022/ prison serviceIncarcerated minors

4.2 %This figure corre…

i02/09/2022/ prison servicePercentage of untried prisoners

66.4 %This figure does…

i02/09/2022/ prison serviceDeath penalty is abolished

Safeguards

Admission and evaluation

All inmates are admitted to prison with a valid commitment order

The Correctional Code stipulates that a person may only be held prisoner pursuant to a sentence or a judgement of conviction, a detention warrant, an arrest warrant or a writ of capias, or in the case of imprisonment for debt. Detention or admitting a person into a correctional facility for any other reason is considered arbitrary detention and is punishable with disciplinary and/or criminal sanctions (Correctional Code, Articles 2 and 3).

Civil society organisations have signalled numerous cases of arbitrary detention.

Apprehensions in several cases relating to national security have raised concerns about the legitimacy of detention orders. In some instances, people summoned or suspected in a case were suddenly taken in for questioning without just cause for arrest. These people were arrested outside of the legal process, without a requisition from the public prosecutor’s department or the investigating judge.1

Fédération internationale des ACAT (FIACAT), “Alternative report of FIACAT and ACAT Congo for the adoption of a list of items to be addressed before presenting the report on the Congo, 129th session”, 8 June 2020, pp. 11-13 (in French). ↩

Prisoners can inform their families about their imprisonment

The Correctional Code stipulates that all prisoners must have the opportunity and the means to immediately inform their family, or any other person they may designate to be contacted, of their detention, prison transfer, judge-ordered transfer1 and any illness or serious injury (Article 77).

The International Federation of Action by Christians for the Abolition of Torture (Fédération internationale des ACAT, FIACAT) and ACAT Congo report that the registers indicating personal details and the date and hour of entry into custody are not regularly updated in public security stations or gendarmeries. People spend months there before being placed in pre-trial detention facilities.

“[…] In practice, these registers are poorly maintained – sometimes the ‘register’ is merely a sheet of paper on which some of the relevant information has been recorded – if they exist at all. This practice often complicates matters for those searching for missing relatives or relatives arrested at random by police officers from an unknown station. In these cases, the family has to make the rounds at all the police stations, and the officers then have to call roll to see who is in the jail,” state FIACAT and ACAT Congo.2

The transfer of a prisoner to another correctional facility at the request of a judge, for example in the event of a hearing, inquiry or appearance. ↩

Fédération internationale des ACAT (FIACAT), “Alternative report of FIACAT and ACAT Congo for the adoption of a list of items to be addressed before presenting the report on the Congo, 129th session”, 8 June 2020, p. 12 (in French). ↩

There is a reception area for arriving prisoners

in no facilities

A copy of the prison regulations is made available to the prisoners

no

The Order dated 15 September 2011 established an internal set of rules for the country’s remand prisons.

The country’s new Correctional Code, established by the Law dated 20 April 2022, provides a model for rules and regulations in correctional facilities. It also stipulates that prisoners must be informed, upon their arrival, of the applicable rules for that prison facility. These rules must remain accessible for consultation for the entire duration of detention. Prisoners must also be informed of their options for recourse and requests (Articles 19 and 75).

These provisions of the Correctional Code are not respected at this time. The incarcerated are often unclear on the conditions of their detention.

The criteria for cell assignment vary from one remand prison to another due to the lack of a regulatory framework. In the remand prisons of Brazzaville and Pointe-Noire, “VIP” cells are available for prisoners with financial means and notoriety. The material conditions there differ greatly from those in the standard dormitories. For example, each “VIP” prisoner has access to a bed, a television and a mosquito net. They are spared the unhealthy conditions of the overcrowded dormitories.

Access to rights

Prisoners can be assisted by a lawyer throughout their incarceration

The law provides for partial or comprehensive legal aid for prisoners who do not have sufficient financial resources.

Comprehensive legal aid is reserved for people whose monthly resources are equal to or less than minimum wage. Partial legal aid is available for people (Law dated 20 January 1984 on the reorganisation of legal aid, Article 5):

- whose income is less than or equal to 50,000 XAF (€76)

- whose income is between 50,000 XAF and 80,000 XAF (€122) and who have three dependants.

In practice, duty lawyers are only consistently available for people involved in criminal cases and for minors. Associations have reported a severe shortage of lawyers. Many of them practise in Brazzaville and Pointe-Noire. The most underprivileged prisoners reportedly have little or no access to lawyers.

Prisoners have access to a legal aid centre

no

The provisions of the Correctional Code on this topic do not seem to be applied. Several human rights organisations explain that it is very difficult to send prisoners information on access to legal services. The organisations face numerous obstacles to enter prison facilities. They are therefore constantly adapting and seeking innovative solutions to get around their lack of authorisation and help prisoners.

National regulations state that solicitors may visit their clients every day between 7.00 and 16.00 (Rules and regulations for remand prisons, Article 12). In practice, these meetings are not always held in an appropriate environment for ensuring confidentiality.

Physical integrity

Deaths in custody are logged in a register

This information is not made public.

Number of deaths in custody

Data not disclosed

The Congolese Human Rights Observatory (Observatoire congolais des droits de l’Homme, OCDH) stated that around 30 deaths occurred between 2017 and 2018. Nine of these deaths occurred at the prison of Ouésso. The OCDH attributes these deaths to poor prison conditions, in particular the dilapidated state of the buidings and the lack of food.

Number of deaths attributed to suicide

Data not disclosed

Death rate in custody (per 10,000 prisoners)

Data not disclosed

Suicide rate in custody (per 10,000 prisoners)

Data not disclosed

National suicide rate (per 10,000 inhabitants)

0.65

The prison service must notify a judicial authority for

all deaths

Facility management is required to open an internal inquiry and to report all deaths, disappearances and serious injuries to the public prosecutor and the attorney general for the jurisdiction’s Court of Appeal (Correctional Code, Article 29).

The prison service is required to treat human remains with respect and dignity. Prisoners’ remains are released to next of kin in a timely manner, once the inquiry is over (Correctional Code, Article 30).

Numerous organisations have reported cases of torture, violence and ill-treatment against prisoners. These practices seem to be particularly widespread in police stations and gendarmeries.

The FIACAT and ACAT Congo report that acts of torture are still practiced despite being prohibited. They say the torturers are protected by their superiors. An inquiry led by ACAT Congo into the two most overcrowded detention centres, Brazzaville and Pointe-Noire, revealed that “81.41% of people surveyed at these two prisons who had been detained in public safety stations or gendarmeries had been tortured or subjected to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment”.1

The OCDH provides information and assistance to dozens of people who have undergone torture or ill-treatment, as well as to relatives of those who have died. Much of the abuse occurs following arbitrary arrests by police forces.

Fédération internationale des ACAT (FIACAT), “Alternative report of FIACAT and ACAT Congo for the adoption of a list of items to be addressed before presenting the report on the Congo, 129th session”, 8 June 2020, p. 11 (in French). ↩

The prohibition of torture is enshrined in the Constitution and the legislation

only in the Constitution

The Constitution prohibits all acts of torture as well as cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment (Article 11). These provisions are also included in the Correctional Code (Article 78). Facility management is required to report all acts of torture as well as cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, even if no complaint was filed, to the public prosecutor and the attorney general for the jurisdiction’s Court of Appeal (Correctional Code, Article 29).

The Criminal Code does not prohibit torture. The code has not been reformed, despite repeated announcements to do so since 2008.

The United Nations Convention against Torture (UNCAT) was

ratified in 2003

United Nations, UN Treaty Body Database, Human Rights Bodies _ Ratification Status for Congo

No torture prevention policy has been implemented by the authorities.

Torture is not defined in any legislative or regulatory provision. Civil society organisations argue that the absence of a definition creates obstacles for conducting inquiries and prosecuting the perpetrators. “Inquiries are rare and do not always meet the requirements of independence and impartiality,” noted ACAT Congo in a 2020 report. The victims fear retaliation and do not, in practice, have a means of recourse.1 This discourages them from filing a complaint and trusting the judicial system.2

Fédération internationale des ACAT (FIACAT), “Alternative report of FIACAT and ACAT Congo for the adoption of a list of items to be addressed before presenting the report on the Congo, 129th session”, 8 June 2020, p. 9 (in French). ↩

Act Together for Human Rights (Agir ensemble pour les droits de l’homme), Association for Human Rights and Prison Life (Association pour les droits de l’Homme et l’univers carcéral), Congolese Human Rights Observatory (Observatoire congolais des droits de l’homme), “Report on Descriptions of Torture in the Republic of the Congo for the United Nations International Day in Support of Victims of Torture”, 26 June 2017, p. 19 (in French). ↩

Number of recorded violent acts between prisoners

Data not disclosed

FIACAT and ACAT Congo are alarmed by violence in detention. The two organisations reported in 2015 that arriving prisoners, who are primarily young, “experience trauma from their first moments in prison. They are beaten and mistreated by the ‘senior’ prisoners before being placed in their cells.” The organisations describe this practice as a sort of “baptism”.

The number of security staff is very limited, and an informal, parallel hierarchy exists among the prisoners. “The oldest or toughest prisoner assumes responsibility, dictating the schedule and sometimes imposing fines or even sanctions on other prisoners. He also receives tributes from other prisoners hoping to avoid mistreatment.”1 A former prisoner told Prison Insider in 2022 that each dormitory of the Brazzaville remand prison has a cock of the walk, a sort of boss. According to this former prisoner, the cock of the walk was appointed by prison management or the guards.

The Order dated 15 September 2011 establishing the remit and organisation of the DGAP’s services and offices, (Article 39) prohibits fighting, verbal abuse and all forms of violence.

Fédération internationale des ACAT (FIACAT), ACAT Congo, “Joint alternative report by FIACAT and ACAT Congo on the implementation by Congo of the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment”, March 2015, p. 34 (in French). ↩

Complaints

Prisoners can send requests or complaints to the prison service, the public prosecutor, the sentence enforcement judge or any other competent authority. The prison service is required to pass along these requests or complaints to the requested authority with proof of delivery (Correctional Code, Article 109).

These provisions are not respected. The existing systems do not allow prisoners to file complaints against the prison service, whether for ill-treatment or acts of torture, or regarding prison conditions. The high rate of illiteracy among the prison population is an additional obstacle.

No specific independent body exists to handle complaints. Civil society organisations are in the process of identifying and assisting victims of ill-treatment and torture to address this issue.

National Preventive Mechanisms and other external control bodies

The Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT) was

signed in September 2008

The Protocol has still not been ratified. During the most recent Universal Periodic Reviews of the Congo, in 2016 and 2020, several countries formulated recommendations relating to the ratification of the Protocol and the implementation of a national preventive mechanism (NPM) against torture.

An NPM has been established

no

A regional body monitors the places of deprivation of liberty

yes

The Special Rapporteur on Prisons, Conditions of Detention and Policing in Africa, one of the oldest special mechanisms of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR), has the power to examine the conditions of detention within the territories of States Parties to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights.

The National Consultative Commission on Human Rights (Commission nationale des droits de l’homme, CNDH), a monitoring body for the protection of human rights, can perform inspection visits of prison facilities and police stations. These visits are then written up into reports and recommendations for the authorities (Ministry of Justice, Ombudsman). These documents are not made public. The CNDH is a state body with little independence. A bill proposing new arrangements for the CNDH’s work is under negotiation. Some civil society stakeholders, including ACAT Congo, are authorised to complete monitoring missions in the country’s prisons.

Sentence adjustments policies

The law provides for a sentence adjustment system

Prisoners may request parole at any time. The request must be addressed to either an investigating judge or a court, depending on the nature of the charges.

Sentence adjustments can be granted by sentence enforcement judges (Code of Criminal Procedure, Article 631).

The sentence can be adjusted as soon as it is pronounced (ab initio)

Sentence adjustments can be granted during the incarceration

The law provides for a temporary release system

Temporary leave requests are examined on a case-by-case basis. “Everyone tries their luck,” says one lawyer. Family matters are often the motivation for such requests.

Number of prisoners who have been granted a presidential pardon or amnesty during the year

Data not disclosed