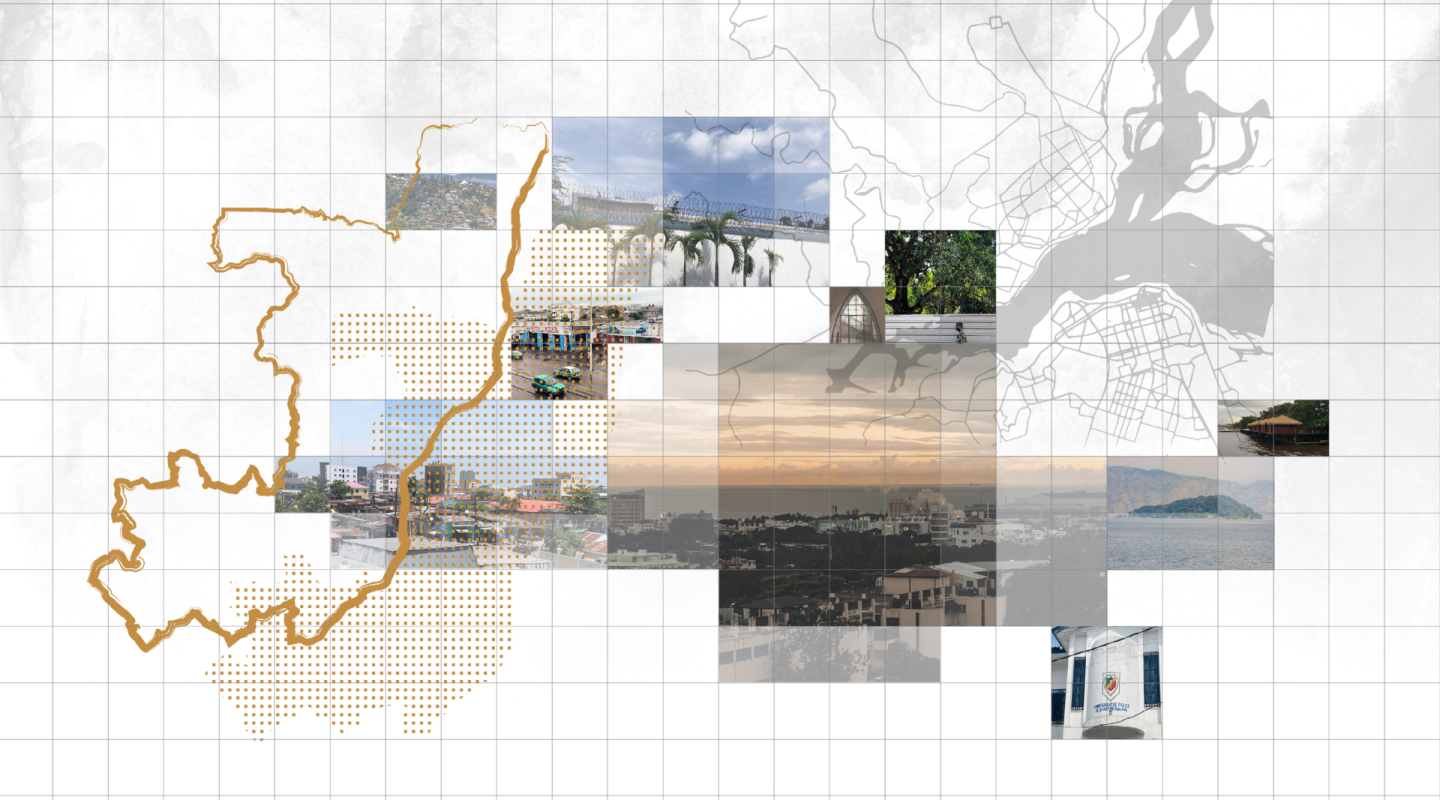

Republic of the Congo

Capital city — Brazzaville

Incarceration rate (per 100,000 inhabit…

i09/2019Country population

i2022Type of government

Human Development Index

0.571(153/191)

i2021/ UNDP, Human development summaryHomicide rate (per 100,000 inhabitants)

Data not disclosed

Name of authority in charge of the pris…

Ministry of Justice, Human Rights and t…since 1991

Total number of prisoners

1,600This figure corre…

i02/09/2022/ prison serviceAverage length of imprisonment (in mont…

Data not disclosed

Prison density

313 %The cited prison…

Total number of prison facilities

An NPM has been established

Female prisoners

2.1 %This figure corre…

i02/09/2022/ prison serviceIncarcerated minors

4.2 %This figure corre…

i02/09/2022/ prison servicePercentage of untried prisoners

66.4 %This figure does…

i02/09/2022/ prison serviceDeath penalty is abolished

Health

Organisation of health care

Ministry in charge

Ministry of Justice, Human Rights and the Promotion of Indigenous Peoples

Every prison facility has a health care unit

The law provides for the creation of health services aimed at receiving prisoners whose state of health requires special care (Correctional Code, Article 18).

Only the remand prisons of Brazzaville and Pointe-Noire have infirmaries. However, these infirmaries do not have the equipment or medications required to address prisoners’ needs. The other facilities do not have care units.12

Fédération internationale des ACAT (FIACAT), ACAT Congo, “Joint alternative report by FIACAT and ACAT Congo on the implementation by Congo of the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment”, March 2015, pp. 8, 45 (in French). ↩

World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT), Collective of Associations against Impunity in Togo (CACIT), ACAT Congo, “Africa and Covid-19 – Health emergency and correctional emergency, Case of the Republic of the Congo”, December 2020, p. 6 (in French). ↩

Number of medical staff (FTE)

Data not disclosed

General health care is provided only at the Brazzaville and Pointe-Noire remand prisons. However, their infirmaries do not have the equipment or medications required to address prisoners’ needs.12

Civil society organisations have criticised the lack of resources allocated to prisoner care. They report that prisoners are in appalling health. Facilities lack healthcare staff – specialists in particular. Medicine is often brought in by families.3

Fédération internationale des ACAT (FIACAT), ACAT Congo, “Joint alternative report by FIACAT and ACAT Congo on the implementation by Congo of the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment”, March 2015, pp. 8, 45 (in French). ↩

World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT), Collective of Associations against Impunity in Togo (CACIT), ACAT Congo, “Africa and Covid-19 – Health emergency and correctional emergency, Case of the Republic of the Congo”, December 2020, p. 6 (in French). ↩

“Report from civil society on the implementation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights”, 4 June 2020, p. 26 (in French). ↩

Access to health care

Health care is free

Healthcare costs for prisoners in facilities without healthcare services must be covered by prisoners, their families or, in exceptional cases, the prison service.1

The associations Act Together for Human Rights (Agir ensemble pour les droits humains) and the Congolese Human Rights Observatory (Observatoire congolais des droits de l’Homme) noted in 2021 that sick prisoners treated themselves at their own expense at the Brazzaville remand prison. The attending physician at the infirmary only issued prescriptions. Both organisations reported that at the Dolisie prison, sick people cared for and treated each other or received assistance from their families.

Fédération internationale des ACAT (FIACAT), ACAT Congo, “Joint alternative report by FIACAT and ACAT Congo on the implementation by Congo of the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment”, March 2015, p. 46 (in French). ↩

Legislation regulating life in detention provides for systems aiming to ensure continuity of care throughout incarceration, including weekly visits from doctors, vaccination campaigns and the creation of care units.

These provisions struggle to be enforced. Civil society organisations have warned of the lack of qualified personnel and necessary resources. The dilapidated state of buildings, overcrowding, and insufficient care and meals all contribute to the outbreak and spread of disease. The state of health of prisoners has been described as “appalling”.

Medication is in short supply in detention. It is often brought in by prisoners’ families.

Hospitalisation is subject to constraints. Only the most serious cases are moved to referral hospitals.1 External healthcare and escort costs must be covered by the sick prisoners.

“Sick prisoners are practically [all] transferred to big cities at their relatives’ expense. Those who are gravely ill will ultimately pass away, either in prison or between prison and the hospital, as hospital transfers are put off to the last minute and lead to numerous deaths. Cases of deaths in prison are reported regularly, but inquiries are never carried out.”2

Fédération internationale des ACAT (FIACAT), ACAT Congo, “Joint alternative report by FIACAT and ACAT Congo on the implementation by Congo of the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment”, March 2015, p. 45 (in French). ↩

“Report from civil society on the implementation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights”, 4 June 2020, p. 26 (in French). ↩

Physical health care

The most prevalent diseases in detention are malaria and skin diseases such as scabies. Numerous cases of malnutrition have also been reported.

The legislation has no specific provision relating to epidemic management. Measures are taken on a case-by-case basis.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, a series of measures was taken by the Congolese authorities in order to limit the spread of the virus. The Minister of Justice, Human Rights and the Promotion of Indigenous Peoples and the Minister of Health established a joint plan consisting of training prison officers in hygiene practices and preventive health techniques. Hygiene products were also made available in remand prisons. Visits from lawyers and relatives were limited during this period (Circular No. 302/MJDHPPA-CAB from the Minister of Justice regarding the adaptation of judicial activity to preventive measures and the fight against the coronavirus pandemic). Visitors were required to perform certain health practices: washing their hands, having their temperature taken and wearing protective masks upon entry into the remand prisons.1

Civil society organisations have warned about the lack of measures to protect prisoners from malaria-bearing mosquitoes. They have specifically criticised the insufficient number of mosquito nets.

World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT), Collective of Associations against Impunity in Togo (CACIT), ACAT Congo, “Africa and Covid-19 – Health emergency and correctional emergency, Case of the Republic of the Congo”, December 2020 (in French). ↩